As I promised in my last post on the classic silent film Häxan, I am going to continue my more general “Creepy Scenes” series in addition to my new silent films one. To that end, this post will return to the horror of the 1970s, which is probably my favorite decade for horror films. And though I will be discussing a film, I’m actually more interested here in the book and the changes that were made from page to screen. There will be lots of spoilers, so you have been duly warned.

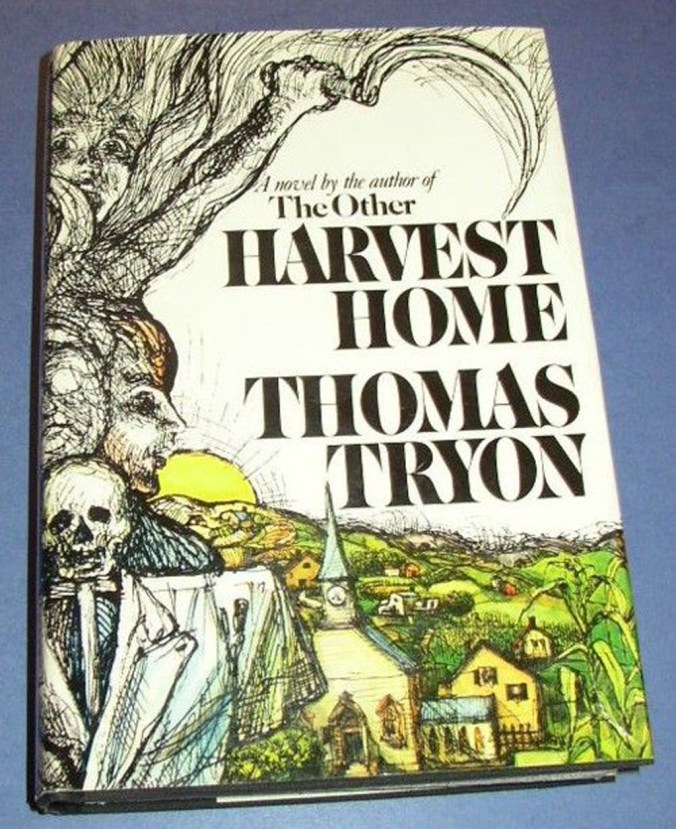

I had been wanting to read Thomas Tryon’s Harvest Home for quite a while, but had somehow never gotten around to it. I adored his 1972 book The Other, and the film adaptation of it is one of my favorite horror films of the decade. A few weeks ago, I was reading a post in a horror Facebook group where people were recommending books that had really frightened them, but didn’t get the attention they deserved. One person recommended Harvest Home, and so reminded, I went immediately to Amazon and bought a used paperback copy for two bucks.

Much like The Other, Harvest Home is a marvelous read, getting under your skin in a way that few books do. In brief, it tells the story of a family from New York City (artist Ned Constantine, his wife Beth, and teenage daughter Kate) who decide to give up their fast-paced city life and get back to the land in the tiny rural New England town of Cornwall Coombe, an agricultural community seemingly (and charmingly) suspended in time. Obviously, because this is a horror novel, the idyllic surface of the community hides a horrific secret that very slowly becomes apparent over the course of the story. Much like The Wicker Man or Stephen King’s “The Children of the Corn,” Harvest Home effectively wrings terror from the clash of ancient earth-worshipping paganism with modern sensibilities.

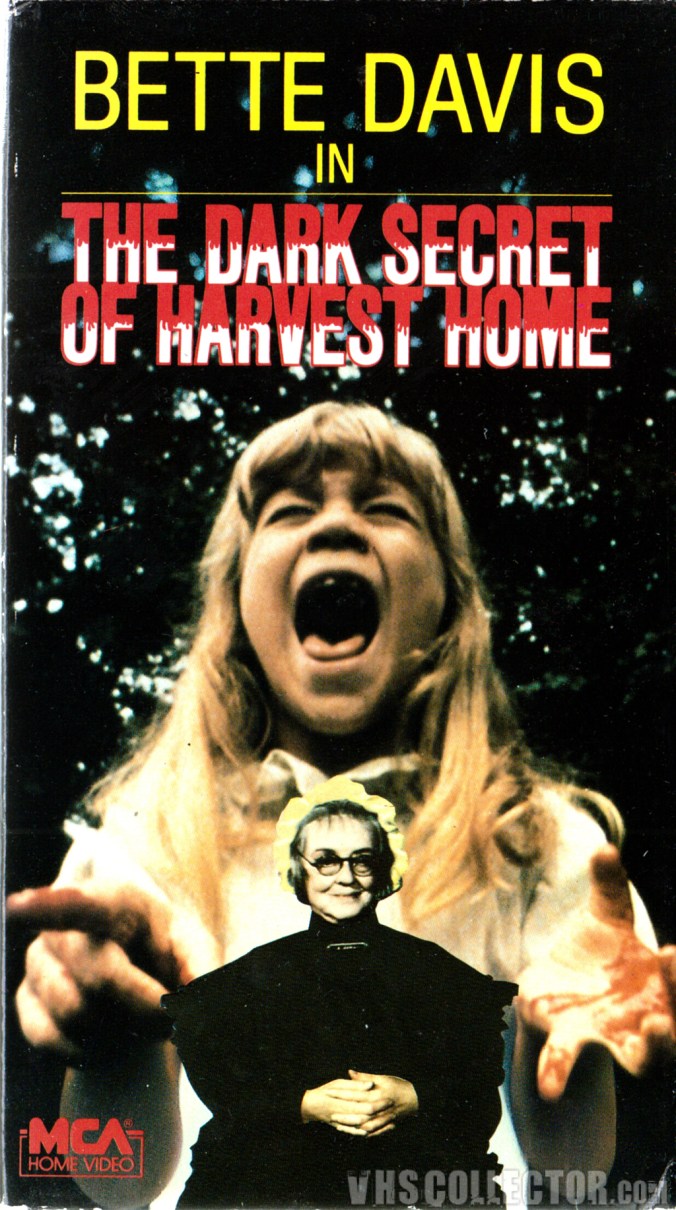

When I was about three-quarters of the way through the book, I began to wonder if there’d ever been a film adaptation of it. Since I hadn’t heard of one, I assumed that even if one had been made, then there was no way it was up to the caliber of The Other. But a quick search of YouTube brought up a four-hour miniseries that had been made in 1978. I initially wanted to finish the book before watching the film so as not to spoil the ending, but I admit my curiosity got the better of me, and one evening last week I sat down and watched the whole four hours in one sitting. If you’re so inclined, you can watch it too, right here:

I finished the book this afternoon, and even though I do wish I had waited to finish it before watching the miniseries, the impact of the book’s ending wasn’t really dulled by knowing roughly what was going to happen; it was still pretty horrific. There were several changes made from the book to the miniseries, obviously, and while I understand why most of them were made, I feel the effectiveness of the miniseries was severely undercut by not following the tone and characterization of the novel.

Though the miniseries seemed to have mostly positive reviews on IMDB, I found it to be profoundly disappointing. There were a lot of well-known actors in it for the time (Bette Davis as the Widow Fortune, a young Rosanna Arquette as Kate, Rene Auberjonois as Jack Stump, a very young Tracey Gold as Missy Penrose), and it had some effective scenes, but it suffered from overblown acting performances and that slightly “off,” late 1970s TV movie sensibility, where everything seemed ridiculously dramatic, and all the conflict painfully forced. None of the characters or the town were portrayed as I had imagined them while I was reading, and the tone of the miniseries held none of the subtly increasing dread of the book. I also found the miniseries difficult to follow; had I not read most of the book before watching it, I think I might have been lost, and turned it off in frustration. A lot of things were left out, or inadequately explained, or, conversely, over-explained. It wasn’t terrible by any means, but I have to say that I’m sort of bummed out that I watched it, because now my experience of the book will be tainted by the movie, and that’s sort of a shame.

One of the things that bothered me the most, and I guess this is a problem with a lot of films adapted from great books, is that much of the subtlety of the book was abandoned in order to make the movie “scarier” or more dramatic. In this case, the changes had exactly the opposite effect. One of the most frightening things about the book is its insidiousness; the horror creeps up on the protagonists (and the reader) so slowly and so inconspicuously that when it does come, it’s tremendously shocking, even though you’ve been expecting it all along. Tryon was a master at this, by the way; his skill in weaving a hypnotic spell around his characters and readers and then pulling the rug out from beneath them is extraordinary. I was just as seduced by the town of Cornwall Coombe as the characters were, and just as horrified when it all went to shit. I felt betrayed just as surely as the characters were, and that is the genius of Tryon’s writing. As I said, that was the most frightening thing about the book. Cornwall Coombe seemed so nice. And not in a fakey, Stepford, something-creepy-is-going-on-here kind of way, but in a genuine, salt-of-the-earth, these-are-really-good-people kind of way. Nothing seemed sinister at all, nothing really seemed off. The people of Cornwall Coombe welcomed the Constantine family in their stoic, New-England-farmers sort of way, they made friends with them, they helped them out, seemingly out of the goodness of their hearts. Sure, there were a few strange things going on, as there are in any small town; those crazy Soakes moonshiners out in the woods, for example, or that grave outside the churchyard fence, or the aggressive attempted mate-poaching of town slut Tamar Penrose, or the prophesying of her mentally challenged daughter Missy. But all of this could be attributed to the quaint, backwards ways of a simple agricultural people who had been doing things the way their ancestors did, unchanging through the centuries. None of it even hinted at the terrifying realities lurking beneath the surface, of how bad things would ultimately get.

By contrast, the TV miniseries made the town seem weird right from the beginning, with lots of significant glances and dialogue that was just too glaringly obvious in its insistence that CORNWALL COOMBE IS A BAD, SCARY PLACE. I understand this to an extent; obviously, when you’re adapting a 400-page novel to a four-hour film, you have to speed up the pacing to get everything in. But I felt like it just didn’t work. The characters seemed too broad and silly, too stereotypical to be effective. Bette Davis made a great Widow, but she was clearly up to something from the start; there was nothing of the kindly, selfless, lovable old woman from the book who is very slowly and shockingly revealed to be evil.

I also had a big problem with the main character of Ned Constantine (whose name was inexplicably changed to Nick in the movie), both individually and in context of his relationship with his wife Beth. In the novel, the entire story is told from Ned’s point of view, and you grow to like him a lot as a person, or at least I did. He’s a good man; he messes up a couple times, sure, but you feel for him, and it seems like his heart is in the right place. He loves his wife dearly, and though some marital problems in the past are subtly hinted at, you get the idea that the pair are not only intensely in love with one another, but are also genuine best friends with abiding respect for one another as people. In the novel, Ned is just as enchanted with Cornwall Coombe as his family is, becomes close friends with several of the villagers, and spends many happy hours drawing and painting residents and landscapes alike. He doesn’t really realize the extent of the horror until very late in the book, and his downfall is therefore terrible and tragic.

By contrast, Nick in the movie seems like a raging asshole from the start, who snaps at Beth pretty much constantly and seems dead set on keeping his snarky distance from the backwards rubes in the Coombe. His relationship with the townsfolk is based on arrogant condescension and outrage; he even summons and berates the constable when he finds the old skull in the woods (which doesn’t happen in the book, where he seems more content to let sleeping dogs lie). As in the novel, he becomes curious about the “suicide” of Grace Everdeen fourteen years before, but unlike in the novel, he decides to write a salacious, tell-all book about it against the wishes of his wife and the other residents, and makes a nuisance of himself asking the townsfolk uncomfortable questions about her death. In the novel, Ned was writing no such book, and in fact was not seeking to exploit the people of the Coombe at all; sure, he was selling some of the paintings he did there to a gallery back in New York, but he was doing just as many paintings for the residents simply because he wanted to, or to give them as gifts. Ned’s loving relationship with his wife and the town in general make the inevitable betrayal of the townsfolk when he finds out their secrets that much more profound. In the movie, Nick was such a cock that I didn’t feel bad at all when his inevitable end came; in fact, I admit I welcomed it, because it felt deserved. That was probably not what the filmmakers intended.

In addition, the character of Beth was portrayed in the film as a neurotic, therapy-dependent harpy who is easily sucked into the traditions of the town and turns on her husband almost immediately. In the book, Beth is a strong, reflective, intelligent woman who seems to have her shit together and loves her husband despite his minor failings. She only really turns against him at the very end, and perhaps understandably so, from her point of view. I just didn’t like the way the movie made their relationship far more contentious than it was in the book, seemingly for the sake of cheap drama. For example, in the book, when Beth tells Ned that she wants another baby, he is nervous and uncertain, of course, but receptive to the idea, and genuinely pleased when she tells him that she’s pregnant. In the movie, she tells him her wishes for a child and he screams at her that there’s no fucking way (not in those words, but y’know). He does apologize when she (seemingly) gets pregnant, but still, the stench of his assholishness lingers.

There were some other niggling changes that bothered me quite a bit. Missy Penrose, the prophesying child, is a terrifying figure in the book, with her creepy pronouncements, her creepier corn doll, and the way all the townsfolk seem to look to this profoundly retarded but “special” child for guidance. When Ned happens to spy upon the ritual of her inserting her hands into the bleeding guts of a newly slaughtered lamb and then laying her bloody hands upon the cheeks of the chosen Young Lord, it’s a seriously chilling moment. In the movie, Tracey Gold’s awkward and overdone performance turns Missy into a shrieking joke.

In the movie, neighbor Robert is simply blind, with white eyes; in the novel, his eyes have been totally removed, which has far more horrifying implications in the context of the story. Likewise, Ned’s fate at the end of the movie is that he’s simply been blinded as well, but in the book, his tongue is also removed (as Jack Stump’s was, providing some nice continuity).

I was also kind of surprised that one of the most shocking scenes in the book was partly left out. In the movie, Nick gets ragingly drunk at the husking bee and runs off after he pisses off the townsfolk by pulling his daughter out of the dance. Ending up in a stream, he is approached and seduced by Tamar. Angered by her aggressive advances and his helpless lust, he lamely attempts to drown her, but does not succeed. She tells no one about this. However, in the book, that scene plays out a bit differently. Ned, who has discovered the town’s betrayal but has so far not really acted upon his discoveries, has an argument with his wife after she doesn’t believe his accusations against the people of the Coombe. He wanders off to the woods, totally sober and in broad daylight, and ends up swimming in the stream. He is approached by Tamar, who begins to work her feminine charms. He loathes her because he knows now that she is the one who not only murdered Grace, but removed Jack’s tongue, but he is equally repulsed by his own uncontrollable lust for her. He wants to kill her, and forces her down in the mud, where he brutally rapes her, wanting to obliterate her with his sexuality. It’s a horrifying scene, because violent rape is PROFOUNDLY out of character for him, but it’s scary precisely because it demonstrates how thoroughly the town has affected him and trapped him, and how powerful is the pagan feminine force working through Tamar. He realizes during the rape that he cannot kill Tamar, and that she has triumphed over him because he has given her exactly what she wanted. She subsequently tells the Widow of the rape, Ned’s wife finds out, and thus his ultimate fate is sealed. I suppose it’s understandable that a TV movie wouldn’t want to show a brutal rape, and now that I think about it, the rape wouldn’t have had the same impact in the movie since Nick was such a jerk that a rape wouldn’t have been out of character for him. In the book, I was astounded by the turn of events; in the movie I just would have been, “Eh, par for the course, I suppose.”

I realize I went on and on, but in brief, I can’t really recommend the miniseries. Read the book instead; it’s phenomenal. And until next time, Goddess out.