If you’ve done even a cursory reading of my other blog posts in this series, you’ll know that the films and scenes I tend to write about are not focused so much on shock or gore as they are on conveying a sense of deep, lingering unease. I feel that movies and scenes that can accomplish this feat successfully are much rarer, for instilling a lasting dread in a viewer is always going to be far more difficult than simply making them jump in their seats or showing them something that turns their stomach. As I mentioned before, I’m not going to belittle horror films that take the easy way out; I’ve enjoyed a great many of them, after all. But my favorite horror is always going to be predicated upon that tightening noose of apprehension, that eerie, nightmarish imagery that sticks with you for sometimes years afterward, that subtly creeping menace that makes you almost regret ever even watching the thing in the first place.

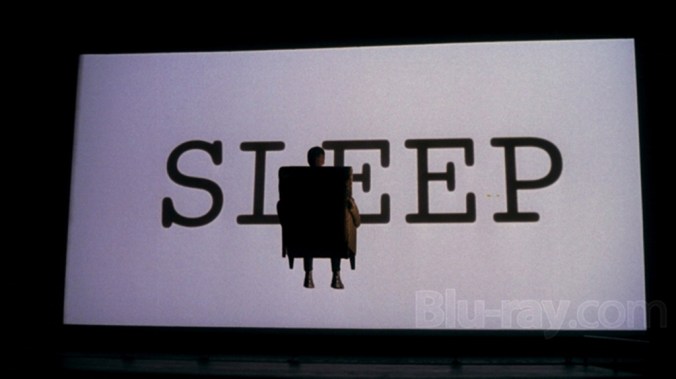

As a case study, I now present a discussion of what I feel is one of the finest horror films of the 1970s. It’s a critically adored piece of filmmaking, but I definitely feel that it sometimes gets short shrift in the “popular” culture of horror films. Part of this may be due to the fact that it’s British, and perhaps more restrained and adult-oriented than the usual horror fare; in fact, it could almost be classified as an “art film.” Part of it may be due to its fractured, confusing narrative and its obsessive repetition of themes. Whatever the reason, though, I hope that those of you who have never seen it will sit down in a darkened room and give it a chance, because I guarantee that you will be in for a truly unsettling experience. One caveat, though: if you’re going to watch it, you might want to wait to read my recap until afterward, because I’m going to spoil the hell out of it. With that warning, let’s continue, shall we?

1973’s Don’t Look Now was based on a short story by Daphne du Maurier (who also wrote Rebecca and The Birds, both of which, of course, were adapted to film by Alfred Hitchcock) and was directed by Nicholas Roeg, an idiosyncratic filmmaker known for such works as Performance, The Man Who Fell To Earth, and the Roald Dahl adaptation The Witches. Roeg’s signature directorial style (and also his visual style, as he started out in the biz as a cinematographer) is all over Don’t Look Now, from the disjointed plot construction to the recurring instances of symbolism. It’s definitely a film that rewards multiple viewings and reveals hidden layers with each rewatch.

Ah, an innocent little girl skipping along right next to an ominous body of water. What could possibly go wrong?

In brief, Don’t Look Now is the story of a married couple, John and Laura Baxter (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie) who are grief-stricken after the accidental drowning death of their daughter Christine (Sharon Williams). To help deal with their loss, John accepts a job restoring an old cathedral in Venice, and the couple move from England to Italy in order to get away from their painful memories.

But naturally, things never work out that simply in a horror film. They have only been in Venice for a short time before Laura is approached by two sisters, one of whom is a blind psychic, in a restaurant bathroom. The psychic tells Laura that her daughter is with her and is happy, even describing the distinctive red raincoat Christine was wearing when she drowned. Laura is overjoyed at the news and believes unreservedly, but John is far more skeptical, and gently tries to discourage Laura’s “fancies.”

However, it soon becomes clear that something untoward is going on, no matter how skeptical John may be. Not only is there a murderer running loose around Venice, but John begins seeing fleeting glimpses of what appears to be a child in a red raincoat around the city. Laura, still heartened by the psychic’s pronouncement, agrees to go to a seance held by the two sisters, at which they tell her that her dead daughter has informed them that John is in danger. John gets angry at all of this psychic nonsense, and he and his wife have a blistering argument where much of their resentments about their daughter’s death come to the fore.

The next morning, they receive a phone call. It turns out that the couple’s son, who is at a boarding school back in England, has been injured in a fall. Laura immediately leaves Italy to tend to him, while John stays behind. Strangely, though, John sees his just-departed wife later that very same day. She is dressed in mourning and standing on a funeral boat in the canal, along with the two weird sisters. He passes her in another boat, and calls to her, though she doesn’t seem to hear him. Confused by her presence when she is supposed to be in England, and concerned about the murders happening around the city, he calls the police and reports her missing. Suspicious police decide to have John tailed instead, as he combs the city for any sign of his wife or the sisters he saw her with. Then, in a moment of clarity, he calls his son’s boarding school and is informed that Laura is there, and had arrived precisely when she should have, judging from the time she left Italy. Severely confused now, John informs the police that his wife is fine and not missing after all. Then later, in the street, he sees the red-clad figure again and chases after it. It should go without saying in a movie like this, but it doesn’t end well.

Director Roeg is a master at fostering a bizarre sense of dislocation in the viewer, but also at wrenching a cloying sense of menace out of every frame in this film. He does this through means both obvious and insidious. First of all, whenever Italian is spoken in the film, Roeg chose not to subtitle it, so that a non-speaker watching the film would feel just as adrift and confused as the characters. Secondly, he plays heavily on the theme of precognition, refusing to make clear whether what we are seeing on screen is happening in the present, the past, or the future, and deliberately chops up the narrative so that it is presented to us in a largely non-linear way. Thirdly, he uses several recurring motifs as portents of disaster: water, glass breaking, the color red, falling objects and people, the sense that “nothing is as it seems.” There is a constant sense of being stared at by hostile-seeming bystanders, there are subtle references to the murders which are never explicitly shown, and just an overall sense of displacement that contributes to the feelings of loss and relationship breakdown that the characters are experiencing. Roeg also makes great use of the dark, gothic back alleys of Venice to ramp up the creepy factor.

Several scenes stick out, but there are really only two that I’d like to briefly discuss. And before you get your hopes up, no, one of them isn’t the VERY explicit sex scene that caused so much controversy when this film came out in 1973. I may discuss it one of these days if I ever do a series on oddly hot moments that inexplicably turned up in horror films, but for now, let’s keep to the scary. Sorry, horndogs. 🙂

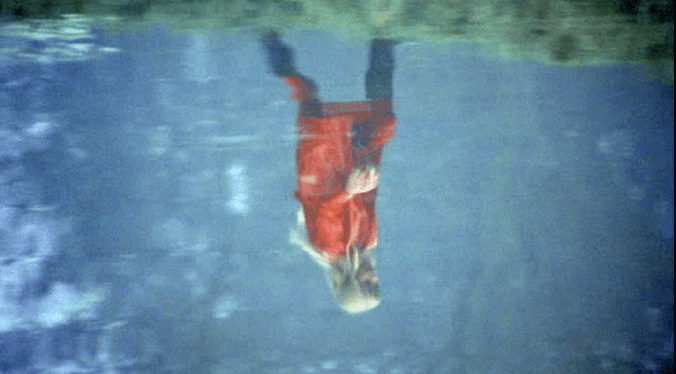

The opening scene is fantastic in establishing many of the themes explored in the film. The family is still in England at this point, and the daughter is not yet dead. Christine, in fact, is playing out in the yard in her red raincoat, while her brother idly rides his bicycle not far away. Inside the house, John and Laura are sitting before the fire. Laura is poring through a book looking for the answer to a question Christine asked her about frozen bodies of water (there’s one of those motifs), while John is looking through slides of the cathedral he is going to be restoring. In one of the shots, he notices a red-hooded figure seated in a pew before a stained glass window. He looks at the slide through a magnifying glass, and suddenly we see what looks like a red arm extending from the figure, though closer examination reveals that it is a tendril of blood, eerily working its way across the slide. The sight of the blood gives John a moment of precognitive dread, and he bolts from the house and out into the yard. Unfortunately, he is too late to save Christine, and is reduced to dragging her lifeless body from the pond and howling in agonized grief.

The second scene I’d like to focus on is the final one, in which all of the director’s leitmotifs culminate in one of the most unsettling sequences in horror cinema. John has seen that elusive red-hooded figure again as he is walking in the street, and begins to chase after it. The blind psychic, of course, has had a vision that John is in mortal danger, and Laura, who has returned from England, begins to run after him. He follows the figure up a spiral staircase to the tower of a cathedral. Laura cannot get in, and is reduced to reaching through the locked gates and yelling for him. John opens a door, and sees the little red-hooded figure standing against the wall, with its back to him. He thinks he hears it crying, and he tells it that he’s a friend, that he won’t hurt it. “Come on,” he says, encouragingly. There is another shot of Laura reaching through the wrought iron gate and calling for him, and then a flashback of the photographic slide with the red-hooded figure sitting in the pew. And then, the red-hooded figure turns around, y’all.

Not a pretty little blonde-haired girl at all, is it? No, it is a disturbingly wizened little woman. She approaches John, shaking her head, and then there are intercut shots of the blind psychic screaming, of the Baxters’ son running across their yard in England, of John embracing a stone gargoyle. “Wait,” says John, and then the tiny, terrifying woman, who in case you hadn’t figured it out is actually the serial killer running loose around Venice, pulls a cleaver from her pocket and thunks John right in the neck. There is a confusing array of images encompassing the past and present: John falling backward, Laura screaming, John holding his dead daughter in the pond, Christine’s red ball, John holding his wife’s hand in a restaurant, a mermaid brooch one of the sisters had been wearing. It’s all set to the discordant sound of church bells clanging. John’s life essentially flashes before his eyes as he lies there and bleeds out upon the floor.

And thus John, who spent the entire film discounting the existence of precognition (even though he experienced it himself just before Christine’s death), has had his second vision fulfilled, even though at the time he wasn’t aware that it was a vision: when he inexplicably saw Laura and the two sisters on the funeral boat, he was seeing the future, and seeing his wife mourning HIS death, not their daughter’s. A fantastically crafted film all around, and one the Goddess enthusiastically recommends.

Until next time, Goddess out.