scifi

13 O’Clock Movie Retrospective: Escape From New York

Tom and Jenny revisit the work of John Carpenter, reviewing the 1981 dystopian classic!

13 O’Clock Movie Retrospective: Logan’s Run

13 O’Clock Movie Retrospective: John Carpenter’s The Thing

So, over on our 13 O’Clock YouTube channel, the God of Hellfire and I have started a fun new offshoot series, in which we yammer endlessly about some of our favorite horror and scifi movies old and new. Right here is our first installment, discussing our impressions and personal stories about one of our favorite classic films, The Thing. Enjoy!

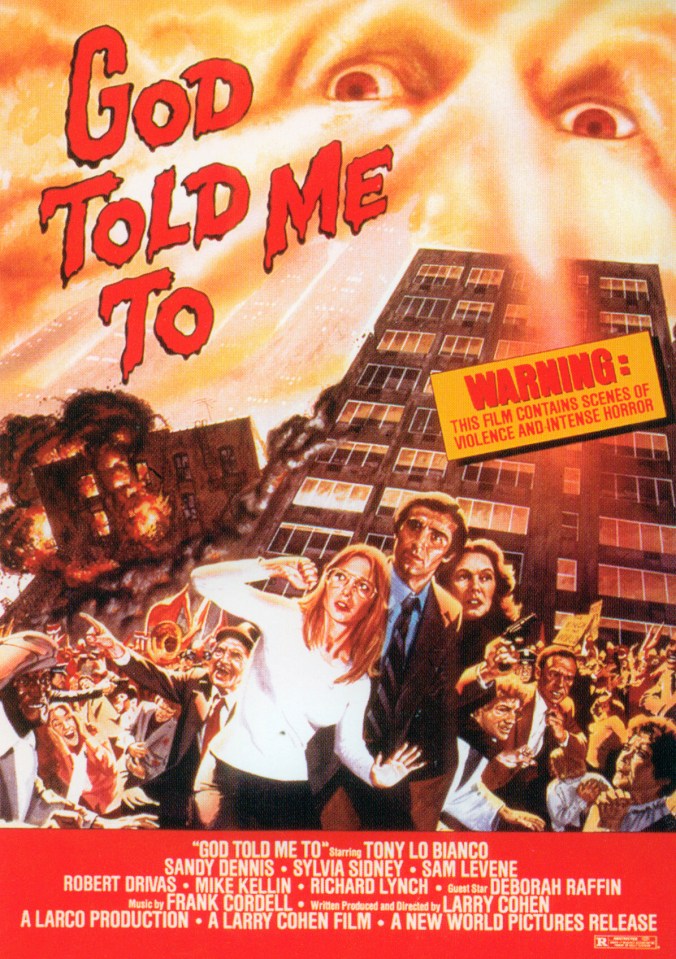

Insane People Seem to be Graced with Incredible Powers: An Appreciation of “God Told Me To”

A horrorific Monday to all of you fiends out there! I’ve returned once again to my favorite horror decade for today’s post, though I’m putting the gialli down for a brief rest so that I can discuss one of the weirder American horror flicks from the 1970s, one that I’d seen pop up on a lot of people’s “best underrated 70s horror” lists but had only just got around to seeing.

Larry Cohen is probably best known to horrorphiles as the director of the It’s Alive killer baby series, as well as a few other cult classics like The Stuff and Q: The Winged Serpent (and, it must be said, one of the better episodes of Mick Garris’s “Masters of Horror” series, the Fairuza Balk-starring “Pick Me Up”). But the film I want to discuss today is one of his stranger and more subversive ones, a film that actually had some pretty complex things to say about religious belief, violence, racial tensions, and gender fluidity. I’m speaking, of course, of 1976’s God Told Me To (also known as Demon, for some unfathomable reason).

The movie centers around New York City police detective Peter Nicholas (Tony Lo Bianco), who is investigating a bizarre series of crimes in which seemingly random people suddenly snap and go on mass killing sprees around the city, always giving the excuse that “God told me to,” right before they meet their own ends. You would think that this film, then, would progress something like a thriller or police procedural, and you’d be partially right, but honestly, if you’ve never seen it, I don’t think you could ever imagine the batshit directions this thing wanders off into. If you’d like to approach this movie cold, though, I suggest you not read any further here, as I’m inevitably going to spoil some key aspects of the plot. You have been warned.

Detective Nicholas lives with his girlfriend Casey (Deborah Raffin), telling her that his devout wife Martha (Sandy Dennis) will not let him divorce her, even though in reality it’s his own Catholic guilt that prevents him. It is his very conflicted faith that causes him to obsess about the ostensibly religion-motivated mass murders occurring regularly around New York, but as he delves deeper into the crimes, he discovers some mightily disturbing facts about the motives of the killers, and also that he himself might somehow be involved in what appears to be some mass hysteria or conspiracy.

And yes, that is indeed Andy Kaufman in his first film role!

It turns out that all of the murderers had fallen under the spell of a mysterious, androgynous cult figure known as Bernard Phillips (Richard Lynch), who seems to have the power of mind control over his subjects. As Nicholas digs into Phillips’ murky past, he finds that Phillips’ mother was supposedly a virgin when she bore him, and further, that she had reported being abducted by a ball of light and subsequently impregnated by what amounted to extraterrestrials. After Nicholas locates the elusive Phillips in a dark basement ringed with flames (obviously a stand-in for Hell), he finds that Phillips wants to control him most of all, but cannot do it, for some reason he can’t fathom.

As the investigation goes on, Nicholas finds that Phillips’s history mirrors his own; the detective’s own mother was also knocked up by visitors from beyond the stars, and the only reason that Nicholas wasn’t aware of it was that his human genes turned out to be more dominant than the alien ones. In the final battle between the half-alien “siblings,” Phillips attempts to persuade Nicholas to impregnate him via a pulsating vagina in his abdomen, but Nicholas ain’t having none of that freaky extraterrestrial action and kills the being, repeating the mantra that “God told me to” when he is later arrested for murder.

I have to say that this is probably the strangest of all the religion-themed horror flicks of the decade, and I haven’t even really scratched the surface of all the insane shit that goes on in this movie. The weirdest thing about it is that it isn’t lurid or funny at all; it’s played completely straight and serious, and is all the more unsettling because of it. God Told Me To is almost like a whacked-out mashup of Dog Day Afternoon, Rosemary’s Baby, Xtro, and the book Chariots of the Gods, and as such, it has many layers of satirical social commentary that are just as relevant today as they were in the 1970s. For example, what is the nature of religious belief, and is it detrimental to the individual and to society as a whole? What is God, and if God supposedly speaks to someone, who’s to say that what God says is right or moral? Where is the line between male and female, and does it even matter? These may seem pretty heavy questions for a little B-horror movie to be tackling, but God Told Me To does so with a surprisingly deft hand. The entire feeling the film evokes is one of a society teetering on the edge of chaos as conflicting forces—of good and evil, masculine and feminine, black and white—all clash in one enormous and yet insidious paroxysm of violence.

It also has some wonderfully frightening scenes, from the fantastic opener as a lone sniper atop a water tower calmly picks off random pedestrians on a city street; to Nicholas’ harrowing visit to Phillips’ mother, who suddenly attacks him in a knife-wielding frenzy; to the movie’s best and most chilling sequence, where Nicholas questions a man who has just massacred his entire family in cold blood at Phillips’ psychic behest. The lucid, almost beatific way the man describes the murders is disturbing in the extreme.

So if you’re a fan of religion-themed and/or gritty urban horror from the 1970s that’s cross-pollinated with a hint of sci-fi, then God Told Me To should definitely be added to your must-see list. Until next time, keep it creepy, my friends. Goddess out.

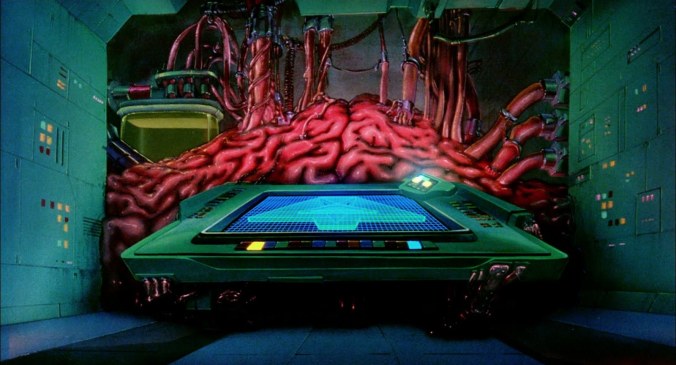

I Too Love the Sound of Cats in Boiling Water: An Appreciation of “Rock & Rule”

I’ve written before (such as right here) about how my formative years corresponded almost perfectly with the rise of home video, cable television, the new wave and post-punk explosion, and MTV, and the film I want to talk about today is sort of a culmination of all those cultural touchstones coming together in one dark, delightful, and musical package. I’ve also discussed a weird animated film before (Jack and the Beanstalk, right here), but the subject of this post is definitely not for kids, and although it’s more sci-fi fantasy than horror, I’m giving it a pass because of its Blade Runner-esque aesthetic, its grandly creepy villain, and a premise that hinges on a Lovecraftian demon invocation. It’s along the same lines as Heavy Metal, though not as raunchy, and it has a rad as hell soundtrack (unfortunately not available) featuring Lou Reed, Debbie Harry, Iggy Pop, and Cheap Trick. I must have seen it at least a zillion times after it came out in 1983, and to this day I have never gotten sick of it.

I’m speaking, of course, of fuckin’ Rock & Rule:

If you haven’t seen this, do yourself a favor and click that linky up there because this movie is awesome and I love it more than it should be legal to love an animated flick about mutated rat-humans in a small-town punk band who are being pursued by a scary magical rock star who needs their singer’s voice to summon an evil being from another dimension. It was the first full-length feature made by the Canadian animation studio Nelvana, who up to that point had been known for making cartoons for little kids, like Care Bears and shit like that. Matter of fact, Rock & Rule itself started conceptual life as a children’s film called Drats!, before taking off in a more adult-oriented direction in light of the success of Heavy Metal and Ralph Bakshi’s animated films. It’s a shame that distribution fuckups with MGM relegated Rock & Rule to box office failure and relative obscurity, because it’s really something of an underrated gem. By the way, if you’re looking for the movie outside of North America, apparently it’s known by the title Ring of Power, which…whatever. Yeah, the bad guy has a magic ring that identifies the frequency of the voice that will summon the demon, but I still think Ring of Power is a little too Tolkein for my liking. YMMV.

Anyway, let’s talk about that bad guy for a bit, because he is easily the best thing about this entertaining slice of new-wave wonderment, and indeed, he might be the best villain in any animated film of the eighties, and no, I’m not exaggerating even a tiny bit. Cavernous and pale, with leonine hair, enormous window-shade eyes, huge lips, and pointed eyeteeth, Mok Swagger (aka Mok the Magic Man) is obviously a post-apocalypic cartoon version of Mick Jagger, with hints of Thin White Duke-era David Bowie thrown into the mix. His singing voice is mostly provided by Lou Reed (except for one song done by Iggy Pop), which is bitchin’, but it’s his speaking voice that really makes the character; Don Francks imbues Mok with such over-the-top, wheedling, gravelly menace that his every pronouncement simply dominates whatever scene he’s in, whether he’s being seductively charming, stern and commanding, or completely losing his shit in a total shrieking meltdown. Just a fantastic voice performance all around, funny and terrifying all at once, that comes damn near to making the movie all on its own. Mok’s songs are great too, very Lou Reed-ian, obviously, and hilariously self-aggrandizing.

Also awesome is Paul LeMat as Omar (note: the original Canadian cut of the film featured a different voice actor, Greg Salata, for Omar’s character), whose dry smart-assery clearly covers some deep insecurities, and Susan Roman as the no-nonsense and kick-ass Angel; the interaction between their two characters is another highlight of the film. Angel was also something of an anomaly in fantasy films of this type from this era, as she was an independent, self-reliant female character with a strong personality who didn’t need the boys to come to her rescue. Sure, she was somewhat sexualized, but in a realistic, empowered kinda way, not in the exaggerated, Frank Frazetta kinda way.

I also adore Debbie Harry doing Angel’s singing voice; “Send Love Through” is a fantastic song, and I love how it bookends the movie, representing something different each time: The first time Angel sings it, she’s desperately trying to reach Omar, who has stalked off stage because he thinks Angel is trying to steal his spotlight, but the second time, she is trying to send back the demon that her voice has summoned, and it’s only after Omar joins her in harmony, singing the song she wrote, that the demon is vanquished. I’m not gonna lie, that final duet with Omar and Angel standing hand in hand before the howling demon, as they sing united in one voice, still kinda makes me tear up a little bit. Is that dumb for a bunch of animated rat-people in a cheesy eighties cartoon? Eh, sue me.

And although I just called it cheesy (albeit in a loving way), I have to say that the animation on this thing was really gorgeous for the time, and very ahead of the curve. It can be a little uneven, true, since it uses a few different techniques (traditionally-drawn frames, rotoscoping, and even a touch of computer-generated animation, which was still very much in its infancy at the time), but the overall look of the film is quite cool, particularly the backgrounds, which as I mentioned earlier have a very Blade Runner look to them. Nelvana took more than 4 years and 300 animators to produce this, and it certainly shows.

In summation, you owe it to yourself to see this. If you don’t, Mok may put a heck on you, or worse, fetch the Edison balls, and no one wants that. So until next time, keep it creepy (and rocking), my friends. Goddess out.

The Goddess’s Favorite Creepy Movie Scenes, or Don’t Fear the Ripper

I thank the universe pretty much every day that I was born at the time I was. My formative years corresponded almost exactly with the explosion of punk and post-punk, the birth of MTV, the home video boom, and the expansion of cable television into more and more homes. Yes, despite my dewy youthfulness, I am, as the kids say, “an old.” And this almost goes without saying, but get off my lawn.

Cable TV, for all you whippersnappers out there, wasn’t really a thing until about the late 70s. I spent most of my very young childhood planted in front of one of those giant faux-wooden-cabinet televisions with a dial that you turned to change the channels, of which there were three (four if you count PBS). Later on we got another channel, Fox (which was channel 35 on the dial in my area), which back in the day showed pretty much nothing but “Sanford and Sons” reruns and Hanna Barbera cartoons.

But then, when I was about nine years old, my dad began working for our local cable company, and one of the perks of his job was that he got all the cable channels for free, including the new pay movie channels, like HBO and Cinemax. Gone was the dial; now there was a large beige box that sat on top of the TV and lit up (oooooooh!). It had a slider that you used to change the channel, and I remember being so excited that there were SO MANY NUMBERS on the slider. SO MANY.

I really only went into this brief history lesson to say that a great deal of the memorable movie experiences of my youth came about because of those magical, commercial-free movie channels we were lucky enough to have. Since HBO and Cinemax were fairly new and untested at that point, they tended to show older, B-grade, or forgotten films, often in rotation several times a day (which explains how I managed to see the wincingly terrible Kristy McNichol musical The Pirate Movie roughly four-hundred times before I hit puberty).

But they showed a heap of great movies too, and one of those is our discussion film for today. It’s not technically a horror film, though I’m not sure what you’d classify it as. A science-fiction thriller, perhaps? Regardless, it was and is a perennial favorite of mine, and true to the spirit of this blog series, it did have a few creepy scenes that stuck with me over the years. Onward.

1979’s Time After Time, directed by Nicholas Meyer, had an absolutely genius premise: writer H.G. Wells (Malcolm McDowell), not content with simply scribbling about time machines, has actually built one that works, though of course he is pooh-poohed by the stuffy upper-class twits he has invited over to demonstrate it to. In the middle of the little snark party, a police constable shows up and tells them that Jack the Ripper has killed again, and clues have led right back to Wells’s home. After a search of the premises, it turns out that one of Wells’s guests and close friends, John Leslie Stevenson (David Warner) has left behind a medical bag containing bloody gloves. Police search for him everywhere in the house, but if you know anything about movies, you know where that slippery serial killer has gone. That’s right, he’s hopped right into Wells’s time machine and boogied right into the future to escape justice. The only mistake he made was failing to snag Wells’s “non-return” key, so that after Jack the Ripper ends up in 1979, the machine automatically travels back to 1893, allowing Wells to follow the killer into the future to try to bring him back.

Much to his confusion, Wells ends up in San Francisco in 1979, not in London as he was expecting. Turns out that in 1979, the machine is part of a San Francisco museum installation about his life. After climbing out of the roped-off machine with as much poise as he can muster, clad in full late-19th-century regalia, he sets off in pursuit of Jack the Ripper. There are some amusing scenes as Wells tries to figure out what the hell is the deal with the mind-bogglingly disco-saturated twentieth century, but these are thankfully not as zany as they could have been, as McDowell brings such grace and dignity to the role that you mostly just kind of sympathize with him, even as you chuckle at his cluelessness.

He eventually finds Jack, all right, but along the way he also finds love. Wells, being no slouch, realizes that the Ripper will need to exchange his (very old) money for modern American currency, so he starts asking at the currency desks of all the nearby banks to see if another old-fashioned lookin’ dude with Victorian-lookin’ money has been in the joint. As luck would have it, the woman managing the desk where Jack changed his coinage is the gorgeous and delightfully forthright Amy Robbins (played by Mary Steenburgen, who actually married Malcolm McDowell the year after this movie came out, though they sadly divorced in 1989). Amy is allllll about Wells’s kick-ass vintage duds, his foxy upper-crust accent, and his gentlemanly manners, and so, being a liberated woman, straight-up asks him out. Wells, taken aback but pleasantly so (he had been an early advocate of women’s rights, after all), handles the situation with remarkable aplomb, and the two become entangled.

Wells tells Amy that the man he’s looking for is a murderer, but obviously does not tell her that they have both come from the past. However, as the story goes on, Amy becomes a target of the Ripper, and Wells is forced to spill the truth in order to save her life. Though she doesn’t believe him at first (who would?), a quick trip three days into the future and a newspaper with Amy’s murder on the front page is enough to convince her. There are a lot of tense moments, many women fall under the Ripper’s knife, but in the end Wells sends the Ripper into oblivion by essentially dissolving his atoms in the machine, and the thoroughly modern Amy has decided that she loves Wells so much that she wants to go back to 1893 with him.

All that aside, let’s get to the scene. I’m going to have to recap it entirely from memory, as I can’t find it on YouTube and don’t have the full movie available to me at the moment, so forgive me if some of the details are incorrect.* As I mentioned earlier, Wells and Amy know the day and approximate time of Amy’s impending murder, since they traveled a few days into the future and saw it in the newspaper. They plan for Amy to simply be absent from her apartment when the Ripper turns up to kill her, but several things conspire to prevent this from happening. For example, the clock in Amy’s apartment has stopped (I think I’m remembering that right), so it is actually much later than she thinks it is. Also, she has been waiting for Wells to arrive so that they can leave together, but he has mysteriously failed to show. Finally, when she realizes that her clock isn’t working and that the time of her demise is nigh, she throws some clothes in a bag and readies herself to get the fuck out of Dodge on her own. As she’s heading for her front door, she sees the doorknob turning. Panicked, she drops her shit on the floor and hides in a closet just as Jack busts into her apartment, big as life and knives a-gleaming.

Unbeknownst to Amy (no cell phones in 1979, yo), Wells has been picked up by the police and is in the process of being interrogated for the killings. See, turns out police find it a little suspicious when you appear out of nowhere – wearing strange clothes, bearing no ID, and calling yourself Sherlock Holmes thinking no one in the future will get the reference – and claim to know where the killer that’s suddenly plaguing the city is going to strike next. Wells tries pretty much everything he can think of to get the police to listen to him, growing sweatier and more desperate with every glance at the clock that shows that Amy’s murder is growing ever nearer. If I remember correctly, Wells first tries to convince the police that he is simply psychic, but after a while he gives them the whole story about traveling from the past to track down the Ripper. The investigator doesn’t buy this for a second, naturally, and keeps hammering poor Wells to admit that he’s the killer. Wells sticks to his guns, repeating over and over that he is from the past, and that Jack the Ripper is in San Francisco, and that a woman is going to be murdered at Amy’s address and WOULD THEY PLEASE JUST SEND A CAR OVER THERE TO CHECK, FOR THE LOVE OF GOD?!? At one point he even confesses to the murders (“I killed them! I KILLED THEM ALL!”) to try to get them off his back. He begs, he pleads, he freaks out, but nothing he does seems to convince them. At last, he looks at the clock and sees that the time of Amy’s murder has passed. He slumps down in his chair, his eyes full of tears. “Please just send a car,” he weeps, defeated, and tells them her address again. “Send a car and I’ll sign anything you like.”

The interrogating officer, apparently moved by Wells’s sincerity and perhaps hoping to get a confession, finally agrees to send two officers over to Amy’s place to see what’s what. The officers arrive and find her door ajar. They peer inside, then one of them turns his head to vomit. For the inside of the apartment is completely painted with splattered blood; it’s just covering everything. And there, lying on the carpet amid the signs of an epic struggle, is a woman’s severed hand.

In the next shot, a somber (and slightly sheepish) police inspector is informing Wells that the murder has indeed gone down as predicted. “Please believe me, I am truly, truly sorry,” says the inspector, while Wells just stares blankly ahead. “You’re free to go.”

Wells, completely grief-stricken, begins wandering the dark, empty back streets of San Francisco. He walks through a park, an absolutely heartbreaking expression on his face. The only sound is the echo of his footsteps.

Then, another sound: the eerie chime of the Ripper’s pocket watch. And then, Amy’s ghostly voice, calling Wells’s name. Wells spins around and sees Amy standing by a wall, looking every inch a spirit or a figment of his tortured imagination.

But no, Amy is somehow alive. “He killed Carol, my friend from work,” she says. “I forgot I invited her over for dinner to meet you.” And then the viewer remembers that indeed, she had asked her co-worker over on Friday night, much earlier the film. We had forgotten all about that, but the screenwriter hadn’t.

Then, there’s a closeup of Amy’s white, terrified face. “The newspaper was wrong,” she intones, in a flat, echoey voice that always creeped me the fuck out. Jack appears from behind the wall, holds a knife to Amy’s throat, and threatens to kill her unless Wells gives him the non-return key. And from there the story builds to its final climax.

I can’t tell you how much I adore this film. It played approximately five times a day on one or another of the movie channels, and every time I happened to stumble across it, I would watch it again. I have to mention that the chemistry between McDowell and Steenburgen is absolutely electric, and it was no surprise to me that they married shortly after the film’s release, as it almost seemed as though the actors were falling in love for real as their characters were falling in love on screen. In addition to that, I just loved the overall story, the gore, the fish-out-of-water element of prissy Wells harrumphing around 1979. David Warner also made a great Ripper: cold, calculating and ruthless, yet still somehow alluring. “Ninety years ago I was a freak,” he says to Wells at one point, as he’s flipping through TV channels showing various violent crimes and war atrocities. “Now, I’m an amateur.”

I wonder if the real Jack the Ripper, were he somehow transported to the modern day, would say the same. Goddess out.

*ETA: A few hours after I wrote this recap, the God of Hellfire was obligingly able to find the entire movie online, and we watched the whole thing through. My memory of the described scene was fairly accurate, but there were a couple of things I got wrong. For example, the actual reason that Amy was still in her apartment when the Ripper came calling didn’t have anything to do with her clock stopping. Rather, she and Wells had been up the entire night before, trying (and failing) to prevent the murder that took place before Amy’s. The following morning, Friday, it is 10:30am when Wells announces that he needs to leave the apartment briefly (he is going against his pacifist principles and going to a pawn shop to buy a gun to defend Amy, though he doesn’t tell her this), but tells her that if he isn’t back in an hour, she should register at the Huntington Hotel and he will meet her there. The freaked-out Amy (who saw the Ripper’s fourth victim being dredged from a canal the night before) unwisely takes a sedative and a few sips from Wells’s flask, thinking Wells will be back in plenty of time to wake her up. But as he is returning to the apartment, he is picked up by the cops, who find the gun he just purchased in his pocket. They haul him away as he is screaming up at Amy’s window. The zonked-out Amy doesn’t hear him, and doesn’t awaken until an hour before her murder was predicted.

I also misremembered Wells trying to tell the police he was psychic. I remembered it that way because earlier in the film, when Wells goes to the police to give them the Ripper’s description, the police ask him if he’s a psychic and he says no. When Wells himself is dragged into the interrogation room and accused of the murders, he tells them the truth right away, and keeps telling it to them until it’s clear that they won’t send a car to Amy’s place unless he agrees to confess. He doesn’t call Amy to check on her, because he has used his one phone call to contact the Huntington Hotel to make sure she checked in (which she didn’t, hence his panic).

Another thing I had mostly forgotten was the splendid chess-like pitting of the overly idealistic and morally upright Wells against the brutally realistic Ripper, who understands all too well that the utopia Wells thought he would find in the future was never going to be anything but a pipe dream. This gave the film a bit of added depth and edge; even though Wells “won” in the end by defeating the Ripper and saving his love, he also had his illusions of human progress shattered, as he realized that the Ripper had been damnably right about humankind all along. “Every age is the same,” Wells tells Amy at the end. “It’s only love that makes any of them bearable.” Truer words, Wells. Truer words. Goddess out, again.