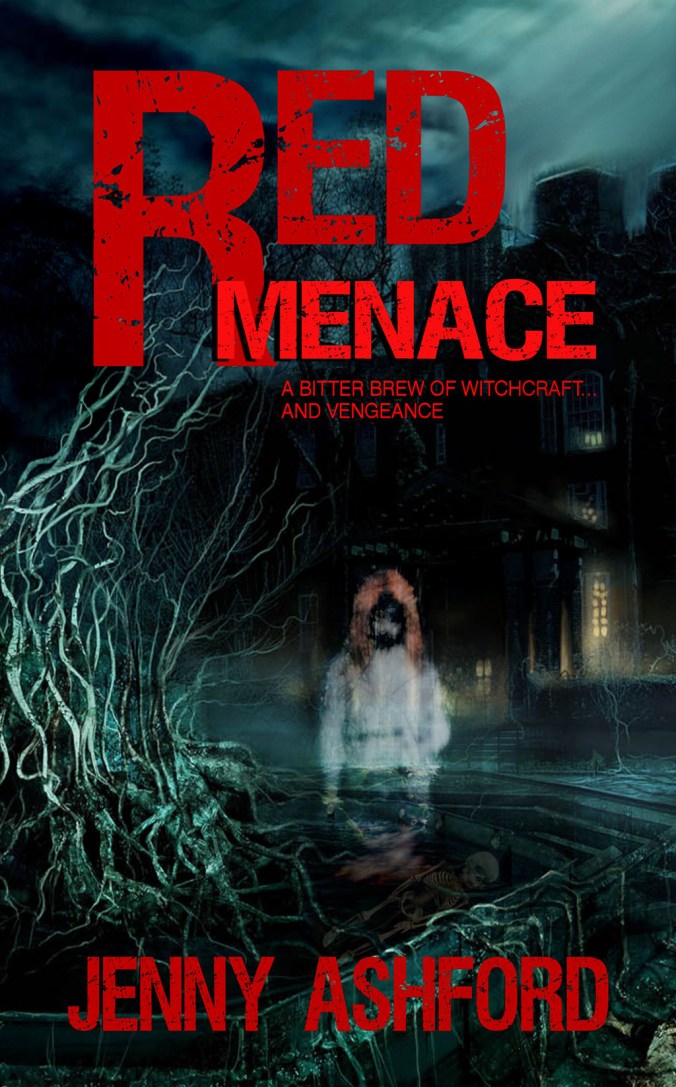

It’s the scariest day of the year, and if you’d like to spend some of this glorious holiday indulging in a bit of creepy reading, please take a few moments to read my 2009 short story, “William’s Pond.” It also appears in my book Hopeful Monsters, so if you like what you read, then why not go all out and purchase a copy today? Thank you, and I hope your Halloween is a haunting, howling scream!

The pond looked dark, even now, even in broad daylight. Muriel remembered it had always looked dark. She had always been afraid of it.

She waded through layers of dead leaves in her worn black flats, keeping her eyes fixed on the still water. The grass around the pond had grown long and wild; Muriel wondered if there were snakes. Her parents had always kept the house and grounds immaculate, and it saddened her to see the neglect, the desolation. Times had been hard for them, since she’d left home. And now they were gone.

A cloud passed over the sun, and in the ensuing grayness Muriel thought she saw a shadow flickering just below the surface of the pond. She stopped and looked harder, but there was nothing. Her parents had always warned her to stay away from the pond, and unspoken but understood in their stern, pale warnings was the knowledge that Muriel’s brother had drowned there, many years ago, when he was no more than a baby. But even if that hadn’t happened, Muriel would have stayed away.

Because when she was a little girl, she thought she’d seen things in the pond.

She scoffed at herself now, standing ankle deep in leaves, wearing a shabby black funeral dress whose cheap fabric stretched taut over her swollen belly. She was a grown woman, with a thirteen-year-old daughter and a second child on the way, a woman who had once been beautiful but now bore the marks of two failed marriages, abandonment, single motherhood. She was no longer the terrified little girl who had peered out her bedroom window under the maple trees and sworn she’d seen shadows moving beneath the water, shadows that looked like people with long, flowing hair. She had left that little girl far behind, perhaps still in this house with its memories.

So why was she still afraid?

“I’m not afraid.” She said it out loud, then reddened and turned to see if her daughter had heard her talking to herself. The house and yard were silent, but her words seemed to echo through the open stillness, coming back to her as oddly warped singsong, a children’s chant repeated like a mantra: Not afraid, not afraid, not afraid…

And she wasn’t, she told herself. She could walk right up to the edge of the pond now if she wanted to, just to show those shadows (those long-haired people who weren’t there) that she was brave.

With every step closer, the shadows seemed to move faster, more erratically. Muriel told herself that she didn’t see them. Instead she thought of her brother’s tiny white body, floating and lifeless, a shock of white against the night-black water. She hadn’t actually seen him drown all those years ago, but her parents had told her what had happened, and after that, she’d seen it every night, in her dreams. The baby’s bluish limbs splayed on the surface of the water, the blacker shadows milling below it, as though making a nest for the egg like little corpse. Muriel had seen it many times, among her many dreams.

She was at the edge of the pond now. The water chuckled and gurgled, then seemed to lunge at her feet with its icy black fingers. Muriel jumped back, then turned around and made her way quickly back to the house.

****

“Do me a favor and stay away from that pond, Angel.” Muriel found herself using the same tone of voice her mother had always used. She smiled, but it was a sad smile, edged with bitterness.

“I know, I know, my almost-uncle died in there.” Angel was only half listening, her head poking into the refrigerator, her tight jeans riding so low on her hips that the waistband of her underwear showed. Muriel had a sudden urge to smack the girl, but she restrained it.

“That’s right.” The fetus in her belly stirred, then kicked, and Muriel winced. Only another week or two, she told herself. She didn’t know if the baby was a boy or a girl; she’d decided to let it be a surprise. Not that it really mattered anyway; its father was long gone, just as Angel’s was. Her luck with men had been little short of catastrophic for as long as she cared to remember.

Angel was smearing jelly on a piece of bread already thickly spread with peanut butter. She sat at the kitchen table across from Muriel, squashing another slice of bread on top of the mess and then bringing the dripping sandwich to her mouth and taking a noisy bite. “Mom, how come you never brought me here?” she asked around a slobbering mouthful.

Muriel didn’t answer at first. What could she say? It wasn’t because she hadn’t gotten along with her parents; she had, even though she’d kept her distance since Angel was born. Was it the house itself that had kept her away, the stately but fading Colonial that had suddenly become a showplace after her brother’s death, the barren fields that had suddenly and copiously borne fruit, the pond with its lapping black life-taking waters? She wasn’t sure. “I suppose I just kind of lost touch with your grandma and grandpa over the years, sweetie,” she finally said. “You know how it is. They had their life, we had ours.”

Angel snorted. “Yeah. Some life.” Despite a face that was still pink and plump with childhood, the girl looked hard, and cynical far beyond her years. Muriel knew that the words were meant to make her feel guilty, and they did, although they made her angry too. She had struggled to give Angel the best life possible under the circumstances, and even though there were times when fate seemed against her, she felt she’d done a decent job. She couldn’t help but resent Angel a little for throwing her failings back into her face.

“I’m sorry.” Muriel wasn’t sure if that was entirely true, but she was too tired to argue. “I should have brought you to meet them. I should have done better.”

Angel shrugged, still chewing, then looked away, out the kitchen window toward the pond. “I wonder how deep it is,” she mused, almost to herself.

****

The baby, a boy, was born less than a week later. Muriel drove herself to the hospital, Angel silent in the seat beside her.

She named the boy William, after her drowned brother, and she brought him home to her parents’ old house and put him in the same room that the first William had slept in before he died. She didn’t know exactly why she did it, although she told herself that it didn’t matter, that her brother’s old room was as good as any other.

William the second was a very good baby, and slept most of the time; nonetheless, Muriel spent hours in the nursery with him, watching him sleep. Sometimes she would sit in the rocking chair by the nursery window and stare out at the pond, which now seemed darker and deeper than ever. Sometimes she thought she saw choppy little waves, disturbances in the middle of the pond, as if as school of piranha were attacking its prey just beneath the surface of the water. She saw this on several successive days, and on each day the disturbance seemed ever so slightly closer to the shore. She wondered if there was a large fish living there, or maybe an alligator.

Muriel moved her bed into the nursery, and slept directly beneath the window.

When William was nearly a month old, there came a night when Angel came to the nursery door, her eyes very white and shiny in the darkness. She was clutching a stuffed rabbit in her arms, just as she had done when she was very small. Muriel beckoned, and the girl came and curled up in the narrow bed next to her mother, deliberately keeping her back to the window. “I thought I saw something,” she whispered, squeezing her eyes shut tight, so the tears popped out through the cracks in the lids. “There was something out there, in the pond.” Muriel stroked the girl’s hair until she fell into a fitful sleep. Then she looked out the window.

There were so many of them—more than she remembered. And as she stared out at them, into their greenish eyes that glowed like fish scales in the night, she realized that she did remember what, all those years ago, had really happened to the first William, her baby brother. The memory was so clear that she didn’t understand how she could have ever forgotten it, how she could have ever believed that the boy had drowned, how she could have believed it so wholeheartedly that she’d had nightmares about it for many years afterwards. She remembered her parents’ chalk-white faces, fearful, horrified—yet was there also resignation behind those expressions, perhaps even acceptance?

The women had come out of the water and ringed the house, just as they were doing now. Their skin was white like fish bellies, and patchy with algae and what looked like barnacles. Their hair hung long and wet and ropy, framing their hideous faces, covering their sagging naked breasts. They were not smiling, but they gave the distinct impression of glee, and Muriel remembered thinking then that if the women opened their mouths, several rows of razor teeth would glimmer in the moonlight.

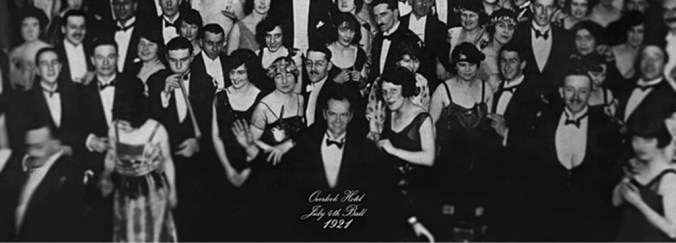

In a moment, Muriel knew, one of the women would step forward, only this single action marking her as the leader. As a girl, Muriel had watched from her second-story window as her parents stepped forward also, meeting the soaking hag halfway. Muriel could not hear what was said, if indeed any words had been spoken. The moon had been nearly full that night, its pregnant yellow form like a spotlight against the purple drape of sky, a stage setting for the horror unfolding by the pond. The fetid smell from the water was so powerful that it seemed to be oozing through the window glass.

Down below, in the yard, her parents were stretching their arms out to the woman, and at the end of their arms lay William, pink and writhing, his little face squinched up in consternation. Muriel thought she could almost hear him wailing, although it might have

been the wind in the eaves.

The woman took the infant from his parents’ grasp, and cradled it, tenderly, staring down at it with her iridescent eyes. The other women gathered around, craning their necks to get a better look. The leader, the one holding the baby, nodded once to Muriel’s parents, as if to indicate that everything was satisfactory, and then she turned her back to them, holding the baby tight against her slick white body. Muriel’s parents turned away also, and headed back

toward the house.

Muriel had kept watching from her window. And watching from the window now, a grown woman, in her old house with her own two children sleeping beside her, she shivered to think what she had seen then, after her parents had turned away. She glanced over at William the second, snoring in his crib, his tiny hands balled into fists on either side of his nearly hairless head. She could not bear it now, seeing both him and the memory of what had happened to her brother, superimposed in her mind like paintings on translucent paper. It was so horrible. And yet…

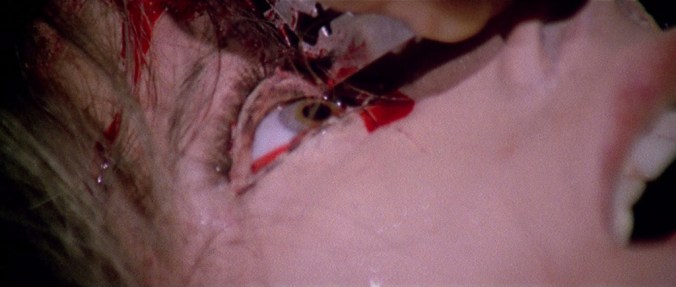

Muriel had seen those women in the moonlight, their scaly backs like eelskins. She had seen them all set upon her brother, the first little William, and even though she couldn’t hear anything, she could see their muscles working as they tore him limb from limb, see their jaws ratcheting up and down as they masticated the tender flesh, see the splashes of blood on their clawlike hands, rendered black by the light of the moon. And she could imagine the sounds of meat rending, of the women grunting with satisfaction and smacking their lips. Muriel saw all these things, and she never told anyone.

The next morning her parents told her that William had fallen in the pond and drowned, and they said no more about it. Muriel had simply nodded and kept silent. Perhaps he had drowned, after all. Perhaps what she had seen from her window had been a dream, nothing more.

The day after that, her parents received word that a distant relative had died and left them a substantial sum of money, enough to pay off all their debts and to make the farm prosperous once again. They were overjoyed, but their eyes were still haunted, and would

stay that way until Muriel left home years later. She could not remember a time when their faces were not hollow and furtive, when their glances did not quickly shift back and forth, constantly searching for something that Muriel could never see.

Angel stirred in the bed beside her, and Muriel held her until she stilled. Then she looked out the window again. The women were still there, a phalanx of corpse-white statues, their sopping hair unmoved by the breeze, their peacock-feather eyes raised to meet hers.

Muriel understood. They didn’t want the baby, not yet.

They wanted to bargain with her.

****

She tiptoed quietly down the stairs, wincing every time the wood creaked beneath her weight. She was afraid, but under the circumstances, quite calm. It’s almost as if I’ve been expecting this, she thought. In a way, she supposed part of her had been.

The moonlight looked almost like chalk where it fell upon the floorboards, and the moldy smell of the pond was like a thick fog. Muriel covered her nose and mouth with her hand. Through the downstairs windows she could see some of the women, silhouetted against the darkness, the moonlight giving them pale glowing auras.

Her stomach clenching, Muriel opened the front door and stepped outside. It was a warm night, but her skin was icy, and daubed with beads of freezing sweat. The leader of these horrible women, these water witches, was still standing slightly outside of the ring, closer to the house, and when Muriel emerged, the hag shuffled even closer through the long grass. Muriel noticed that the woman’s fingers and toes bore bluish membranes of skin between them, like frog’s feet. The sight made her gorge rise.

“You know us.” When the woman spoke, her carp-like lips barely moved. Her voice seemed deep and green and coated with slime.

Muriel opened her mouth to respond, but for a moment no sound came out; her throat had gone completely dry. She coughed, nervously. “I…I remember you,” she finally managed.

“Then you know what we want.” The hag’s eyes glittered like sapphires.

Muriel hadn’t known what she was going to say to the woman, but before she knew it, she was sobbing, begging. “Please,” she said, her vision blurred by the unbidden tears, her voice cracking. “Please don’t take my baby.”

The hag looked at her, the monstrous white face expressionless. “We would of course make it worth your while,” she purred. “Just as we did with your parents.”

Muriel recalled the sudden wealth, the farm’s startling prosperity after that horrific night, and for the briefest moment, she was tempted. Even though she also remembered those empty, haunted looks that had thereafter never left their faces, she couldn’t deny it. She was disgusted with herself.

The woman was still staring at her, and the others remained in their moveless ring, infinitely patient, as though the dawn would never come. And perhaps it wouldn’t, through some of their witchery; perhaps the yellow moon would hang there in the velvet sky until doomsday, until Muriel had finally consented to their desires.

“And what if I don’t…” Her voice hitched, her throat threatened to close, but she forced herself to go on. “What if I don’t give him to you?”

The lead hag’s expression didn’t change, but Muriel got the feeling that the air around her had grown thicker, heavier—it pressed into her nose and mouth, smelling like stagnant water and algae, creeping into her lungs and growing there like fungus. She gasped for breath.

“We will take the boy regardless,” the crone hissed through her white, grouper lips. “Had you given him to us willingly, we would have shown you our gratitude. Since you resist, you will incur our wrath, and the boy will die anyway.”

Muriel was shaking all over, but she tried to sound defiant. “All we have to do is l…leave.” She cursed herself for sounding as frightened as she was. It occurred to her that Angel might have awakened and could be watching the entire scene from the nursery window. She didn’t dare turn to look.

The hag’s lips pulled apart in what might have been a smile on a less inhuman face. Her teeth were small and triangular and close together. A piranha’s teeth. “Our curse will find you wherever you go,” she said softly.

Muriel shook her head, seeing the unending row of white witches’ forms as an indistinct blur in the silvery moonlight. “I don’t believe you,” she said, and the minute the words had come out of her mouth, the suffocating pond fog seemed to lift, and she could breathe again. A moment later she realized she was standing in the yard alone in the middle of the night in her bare feet, and that it was cold, far colder than she remembered it being. The grass was wet between her toes.

A moment after that, she was blinking awake, clear sunlight pouring in through the nursery windows, Angel snoring quietly beside her. Muriel lay very still, relishing the morning and the sensation of rebirth it brought, and then William began fussing and she got out of bed to tend to him.

****

When Angel awoke and came down to breakfast a little over an hour later, she seemed to have no recollection of the night before, or if she did, she was choosing to hide it. She gave her mother a cursory glance before sitting down at the table and tucking into a bagel and an overflowing bowl of cornflakes, all the while scanning the pages of a fashion magazine she held in her free hand.

Muriel watched the girl for a few minutes, William perched in the crook of her arm. “Angel,” she said at last, “it’s time for us to be getting back home. School will be starting in a few weeks, and I’d like to get this house put up for sale before too long.”

Angel barely looked up from her magazine. “Mm hmm. When are we going?”

“Today. There’s really no reason for us to stay around here, is there?”

“Nope.” Angel took a long swig of her orange juice.

William began to squirm, and Muriel moved him to her other arm. “We can stay in a hotel tonight, then tomorrow when we get back to the city we can start looking for another apartment.”

“Okay, whatever.” Angel drank the last of the milk out of her bowl, then left the dishes where they lay and stomped back up the stairs to her room. A few seconds later Muriel heard a door close up there, and then the muffled beat from her daughter’s old stereo.

Did she remember anything? Muriel wondered as she picked up the dishes, maneuvering William’s tiny body to accomplish the task. Perhaps the girl had rationalized the events away as simply a bad dream that seemed ridiculous in the sunlight’s cruel glare. Or perhaps

she had done what Muriel herself had done, all those years ago—completely blocked out everything she had seen.

After the dishes were washed, Muriel put William in his carrier where she could keep an eye on him, then proceeded to pack all of their things into her two battered suitcases. She hadn’t brought much; she hadn’t even intended to stay here as long as they had, though she knew there would be practical matters to be sorted out. She felt guilty that she hadn’t even contacted a realtor or the lawyers about the sale of the property, but then she mollified herself with the thought that William had come along early, and caring for him had been taking up nearly all of her time. This was true as far as it went, but she still couldn’t completely excuse herself. She sighed, resenting William’s father—and Angel’s, for that matter—for leaving her to carry the entire burden alone.

As she packed, she tried desperately not to think of the real reason for their swift departure. She didn’t want to think of it, of what would happen if what the hag said had been true—that the curse would follow Muriel wherever she went. But that was silly, wasn’t it? The women lived in the pond, and surely their influence couldn’t extend far beyond its parameters, could it? Besides, how would they even know where Muriel had gone?

As she folded her clothes and laid them in the suitcase, she noticed that her hands were trembling. She glanced over at William, who had dozed off in his carrier. His black eyelashes fluttered against his cherub cheeks, and his lips pouted outward from his sweet, fat little face. Muriel couldn’t imagine handing him over to those horrible women with their blue-metallic eyes and their dripping piranha teeth. She felt a wave of revulsion and hatred toward her parents for their cowardice, for giving the first baby William to the hags without even a single look back, for accepting the rewards the women bestowed upon them—guiltily, perhaps, but definitively. Why hadn’t her parents fought to keep their son? Was it simply fear, or were they also blinded by their greed, their desire for a better life? Muriel couldn’t remember despising her parents as much as she did in that moment, as she watched her own son sleeping in the early afternoon sunshine slanting through the windows, his tiny fists curled at his sides, his expression slack and peaceful. Yes, I’m afraid of them too, Muriel thought. Maybe even more afraid of them than my parents were. But they’re not getting William. Not this time.

****

By six that evening, they were all settled in a shabby but fairly clean motel room a few miles out of town, almost seventy miles from the farm they’d left behind. If Angel wondered about the abruptness of their departure, she didn’t mention it; the second she set foot in the motel room, she tossed her bags on the floor, kicked off her shoes, and flopped onto one of the two double beds, clicking on the TV with a remote that was bolted to the bedside table.

Muriel wanted to ask Angel if she remembered what had happened the night before, but she didn’t quite dare. The house and its black pond were still too close; she could feel the swampy, rancid tang of them still clinging to her skin. She could ask her about it once they were far, far away, once the place had been sold and hopefully razed to the ground, the pond drained and filled and forgotten. For a moment Muriel almost laughed, thinking of those fearsome water witches choking under tons of bulldozed earth, but then she envisioned the shifting pearly eyes of the hags, the sight of their algae-coated fingers reaching for the first baby William, the animal sounds of them tearing the child into bloodied scraps of meat. Muriel’s laugh dried up in her throat.

She fed the baby, then put him in his carrier and propped him up next to her in the second double bed. He’d been fidgeting and crying for most of the drive here, but now he seemed calmer, and stared at the flickering television screen with rapt attention for a little while, until his lids slowly closed. Angel likewise dozed off, fully clothed and still lying on her stomach on top of the covers. Muriel carefully leaned over and turned off the light above Angel’s bed, then pushed the off button on the remote. In the ensuing darkness and silence, she could hear the steady, comforting stream of traffic rushing by outside, as well as the rhythmic snores of her two children. Orange shafts of light from the streetlamps ringing the parking lot etched lines of fire across the walls.

Muriel was so tense that she thought she’d never be able to fall asleep, but she must have at some point, for some unknown span of time later, she snapped out of an amorphous nightmare to find the room in total blackness—the streetlights appeared to have gone out, and even the sounds of the traffic outside had utterly ceased.

Struggling to fend off the creeping panic, Muriel groped in the dark on the bed beside her, searching for William’s carrier. Her frantic hands met nothing but air, and with mounting horror she realized that the bed she lay on felt cold and strange, as if it were covered with slime.

She tried to cry out, to call to Angel, but her tongue seemed to have swollen, filling her mouth, and all she could manage was a strangled gasp. She turned over on her stomach, reaching up toward the light switch that she knew must be there, only inches from her fingers, but in the darkness she could get no bearings, and her hands simply waved blindly, futile, finding no solid purchase.

Panic had set in fully now—Muriel could feel it immobilizing her limbs, sending her rational thoughts swirling and screaming into the abyss. She was no longer in the motel room anymore, she didn’t know where she was, and William and Angel were gone. The smell of the cursed pond assaulted her nostrils and she gagged, rolling to escape it and falling, landing with a thump on one elbow, which made an upsetting crunch before sending shards of jagged-glass pain into the space behind her eyes.

Moaning, she reached out with her good arm and grasped something that felt like wet fabric—the bottom of a bedspread? She almost cried with relief. She was still in the motel room after all—maybe there had been a blackout, and she had awakened in the middle of it. She hadn’t been able to find William on the bed next to her, but it was very dark—she’d been half-asleep, disoriented.

Regaining her senses somewhat, Muriel used the bedspread to help haul herself into a sitting position. Her elbow was throbbing, possibly broken, but her relief was like a soothing tide, blotting out the pain almost entirely. It was still so dark that Muriel may as well have been staring at thick black velvet drapes hanging inches from her on all sides; not a speck of light penetrated anywhere, and the smell of the pond was still as heavy as syrup.

Sweating and cursing, Muriel pulled herself to her feet, and almost immediately went sprawling, unable to orient herself in a world with no visual cues. She finally stood upright, shakily, not daring to move a step. “Angel?” she called. Her voice seemed swallowed by the immensity of the darkness, but the sound was still so startling that Muriel’s heart skipped several beats.

“Angel!” Louder this time. The girl was a deep sleeper, Muriel knew that, but she was disturbed when she got no answer. She held her breath and listened hard in the blackness, craning her head toward where she thought Angel’s sleeping form should be, but there was nothing. She may as well have been the last human alive, floating in the vast nothingness of space.

And then, for a moment, she thought she did hear something—a rush, a sigh. Muriel flapped her arms desperately around in the blackness, nearly losing her balance again. The sound could have been her imagination, or it could have been Angel or the baby. Somehow she knew, though, in the depth of her gut, that it was neither of these things. She knew that something was wrong.

As she stood frozen in her dreadful certainty, there was another sound that could have been a laugh, and then a blast of frigid air rushed past her face—air that stank of the pond, a thick green rotten stench that brought the water-hags’ countless army clearly into her mind’s eye. She flailed again, almost falling, her elbow protesting with every movement. And her hands finally met something solid, slamming up against it with such force that she nearly screamed.

It was a wall, and Muriel leaned against it, pressing her palms flat against the textured wallpaper, silently thanking gods she had stopped believing in on that night when her baby brother had been taken away. Moving slowly, her heart thudding like a jackhammer in her chest, she felt her way along the wall until her fingers met what could only be a light switch. Crowing with triumph, she flipped it, then had to close her eyes for a few seconds at the sudden brightness.

Before she opened her eyes, she realized that the blackout theory was obviously incorrect. Her body felt as though it were filled with lead.

She opened her eyes, reluctantly. The wallpaper was just as she remembered, beige and speckled with tiny shards like diamond chips. It looked blurry this close up. Feeling as though she were in a slow-motion nightmare, she turned and surveyed the room.

The bedspreads and carpet, both an undistinguished shade of orangish-tan, were now spattered with an olive green, mucus-like slime, a stinking layer of algae-covered seaweed coating the surfaces like rancid frosting. The smell of stagnant water hung so thickly in the air that Muriel almost thought she could see the droplets.

Both Angel and William had completely disappeared.

****

Muriel could barely see through foggy tears of loss and rage. She drove as fast as she dared, barreling down the near-empty highway under a bowl of stars that seemed to shine down on her with mocking indifference.

She cursed herself with every filthy word she could imagine, banging her hands on the steering wheel until the skin on her palms split, until her fingers were slick with blood. Why hadn’t she believed them when they said they’d find her anywhere? Would it have made any difference if she had? And why had she felt as though she were being so brave when it was really her children’s lives she was toying with?

She had no ready answers to these questions, and it felt as though her whole body might explode in her frustration and self-disgust. What else could she have done? Stayed at the house and just let them take William, like her cowardly parents? She could never have forgiven herself if she did that. But she grimly realized as she drove that perhaps her parents had understood something that she had not—sometimes you simply had no choice.

Even though it had only been seventy miles to the motel, it seemed to take forever to get back to the house. Time seemed to be warping and bending in bizarre ways, making her entire perception skewed and dreamlike. She had no idea what time it was when she finally turned down the dirt road toward the farm. It was still dark, but at this point that didn’t mean anything to her—she remembered how the women could make it seem as though the night would never end.

The car tires crunched noisily as she steered toward the driveway, her body performing the function of driving with no input from her brain at all. She made no attempt to conceal her approach; the witches would be expecting her, of that she was certain. She was just as sure

of the fact that she would get William back, or die in the attempt.

There were no lights on in or around the house, and its rambling white structure hunkered in the darkness like a massive ghostly reptile tensing to spring. Just beyond the house, Muriel could see the edge of the pond, the moonlight peppering its gentle ripples. There was no sound at all except for the car’s engine, and when Muriel turned the key, the silence fell like a shroud.

She took a cursory glance around to see if there was anything that could be used as a weapon, but she quickly abandoned the search and got out of the car. Even if she’d had a machine gun, she doubted it would be much use.

Muriel had left the headlights on to guide her way, and as soon as she was clear of the car, she broke into a run, her sneakers crashing through dead leaves and shallow mud puddles. Her elbow felt huge, swollen inside her sleeve, but she tried to ignore the pain. As she stumbled through the yard, she thought she heard a splash, and the smell of the pond came into her nostrils like an intruder, a nearly solid wall of stench. She fought back her revulsion and pressed forward.

Muriel rounded the corner of the house at full clip, and now the pond in its entirety came into her view, huge and seemingly bottomless, its surface flat as black glass. The weeds and grasses at its perimeter stirred in the light wind, and their whispers soon resolved themselves into what sounded like words. Muriel skidded to a halt. She swore she heard a baby crying, very far away. “William!” she called, and her voice volleyed back to her with a sinister, watery tinge.

They came out of the pond like bubbles of acid, their reptilian heads emerging slowly and in perfect synchrony. Muriel watched, horrified but transfixed, feeling as though she was under a spell. Perhaps she even was. The hags’ dripping faces were now clear of the pond’s surface, and al of their eyes opened in unison, the moonlight catching the orbs so that they appeared to be a sea of fireflies or will-o-the-wisps. Muriel wanted to run away but couldn’t, wanted to plunge into the filthy water and tear the hags to pieces, but couldn’t. She could do nothing but stare as they rose from the pond, their scaly flesh sparkling wet, their long hair hanging in straight, shimmering ropes.

And then Muriel’s gaze focused at the middle of the pond. Her legs collapsed beneath her.

Angel was hovering there, her lithe naked body already beginning to bloat and go pale, her brown eyes turning coppery, glimmering in the dark like cat’s eyes.

William was squalling in her arms, his lungs gurgling with pond water.

Muriel tried to speak, but found she had no voice. Her knees dug into the ground, cold mud seeping through the fibers of her clothes. She reached out with arms that seemed to weigh a thousand pounds.

The woman approached the shore, their feet skimming lightly over the water, and soon stood in a well-organized knot in the reeds at the pond’s edge. Angel was afforded pride of place, directly in the center of the group. The other women backed away a respectful distance, giving her room. She held the baby and stared down at her mother.

Muriel shook her head, her lips flopping in futile rhythm. No, Angel, she wanted to say. How could they have done this to you? You can’t do this, not you. Not my Angel.

The girl seemed to have understood her mother’s thoughts, for her eyes flickered briefly, and she glanced down at William with what appeared to be uncertainty. But when she met Muriel’s gaze again, all semblance of the old Angel had disappeared. “They’ve given me power,” she said, and her voice, though seemingly choked with the filth and gravel and slime that coated the pond and everything in it, was as clear as a dagger sunk deep into Muriel’s heart. “They would have rewarded you. This is all that they asked for. Just this.” Angel held the baby out slightly—he wriggled and whimpered, and the women looked down at him with plain lust and hunger in their twinkling eyes.

“We could have been rich and powerful together,” Angel went on, her face a mask of mock regret. “You could have had other babies. Other girl babies. They only want the males.”

Muriel clenched her fists in the mud, trying to will away the vision of impossible reality before her, trying to convince herself that she was still asleep, back in the motel room or back in her old room in this house or even back in their old apartment in the city—anywhere

but crouching on the banks of the black pond that had stolen her childhood from her.

“I’m one of them now,” Angel said, clasping the baby closer to her chest. “William is going to make it official.”

“No…” Muriel managed to croak past the paralysis that stilled her throat.

The women were getting impatient now, eager to partake of the sacrifice of the living infant flesh seductively wriggling before them like a worm on a hook. From among the seething crowd came another voice, and Muriel recognized it as belonging to the leader, the woman she’d spoken to a million years ago, or maybe it was the night before. “It has come to this,” she said in her rattling frog-song. “It is your last chance. Join us now and you will be with Angel forever. Refuse us, and you will die like William, and like your brother before him.”

With the last scrap of willpower she possessed, Muriel raised her head and met the eyes of the hag with her own. A wordless look passed between them.

“The choice is made,” the leader said.

****

The van’s tires crunched up the dirt driveway, sending dozing bugs and lizards scurrying for cover. It was a hot day, midsummer, and the sun beat down like a punishment. Thin tendrils of steam rose from the surface of the pond behind the house.

A young man climbed down from the driver’s side, his hair shining like polished copper. A moment later he lifted a little girl—who looked no more than five, and shared her father’s new-penny hair color and soft, kindly features—down to the ground, where she immediately darted around to the passenger side to meet her mother, who was stepping out of the van with a wistful smile on her face. She scooped up her daughter and looked at the house’s crumbling but still grand façade. There was love in her face, and hope, glowing there like a beacon.

Muriel raised her head a little more above the surface of the pond. Her long algae hair dripped water into her opalescent eyes, but she barely noticed it.

The family had gone inside the house. Muriel gazed up to the second floor, to the nursery window where both Williams had once spent the whole of their short lives. For a second, she was sure she saw a little girl’s face behind the glass, staring back at her in pale, silent terror.

Muriel smiled and submerged her head again, clacking her sharp piranha teeth.