In the midst of royal intrigue and pseudo-scientific machinations, Haydn’s head spent many years traveling outside of his gravesite. The original article I wrote can be found here.

On May 11, 1809, Joseph Haydn slipped quietly into death at the age of 77. War was raging outside as the French laid siege to Vienna, but Napoleon had posted guards at Haydn’s home to spare the composer any danger. A French officer had even come to honor Haydn by singing an aria from The Creation. The relative tranquility that surrounded the composer on his final day, however, gave no hint of the bizarre events in store for Haydn’s remains.

Joseph Rosenbaum and Phrenology

The early 19th century was the heyday of phrenology, a “new science” whose practitioners claimed to measure intelligence and character by examining the size and placement of bumps on the human head. Doctors were becoming increasingly interested in collecting and studying skulls, and particularly liked to get their hands on the skulls of eminent persons, like great philosophers and artists of genius.

Joseph Rosenbaum managed the accounts of the stables belonging to the powerful Esterhazy family of Eisenstadt, Austria. Rosenbaum was a friend of the much older Haydn, and was also keenly interested in phrenology. He never made a great secret of the fact that he wished to study Haydn’s skull, and as he knew his friend was nearing death, Rosenbaum began to make plans to obtain the composer’s head after burial. Since he didn’t want to botch the job when the time came, he decided to do a trial run.

Practice Grave-Robbing

A well-known actress on the Vienna stage, Elizabeth Roose died in childbirth in October 1808. Rosenbaum had not planned to steal her head specifically, but when the opportunity arose, he grabbed it. About a week after Roose’s death, Rosenbaum and friend Johann Peter bribed a gravedigger to exhume the actress’s body and cut off her head.

The friends took their reeking prize to Peter’s home, where they and a Dr. Weiss proceeded to scrape the skin and muscle off the bone, scoop out the rotting brain, and bleach the skull clean by submerging it in quicklime. The experiment was only partly successful; the smell and mess had been far more horrible than Rosenbaum had expected, and lengthy immersion in the quicklime solution left the skull brittle and moldy. Rosenbaum decided that when it came time to swipe Haydn’s head, he would turn to the experts.

Taking Haydn’s Head

Less than a year after the Roose experiment, Haydn died. Shortly after the composer was buried in Hundsthurmer Cemetery, Rosenbaum paid the same gravedigger to purloin the head, which he then handed over to his trusted friend Dr. Eckhart and a team of “corpse bearers” at Vienna General Hospital. Their work on the skull was impeccable, and Rosenbaum could hardly contain his excitement. He had a fancy case made to hold Haydn’s skull; it was black with a glass front, and topped with a golden lyre.

The Prince and the Missing Skull

Rosenbaum and Peter kept possession of the skull for the next eleven years. But in 1820, Nicholas II of the Esterhazy clan, who had been Haydn’s patrons, belatedly decided to honor a family promise to move the composer’s remains from their modest digs at Hundsthurmer to a more spectacular tomb in Eisenstadt. The only problem was that when the body was exhumed, it was, of course, missing its skull.

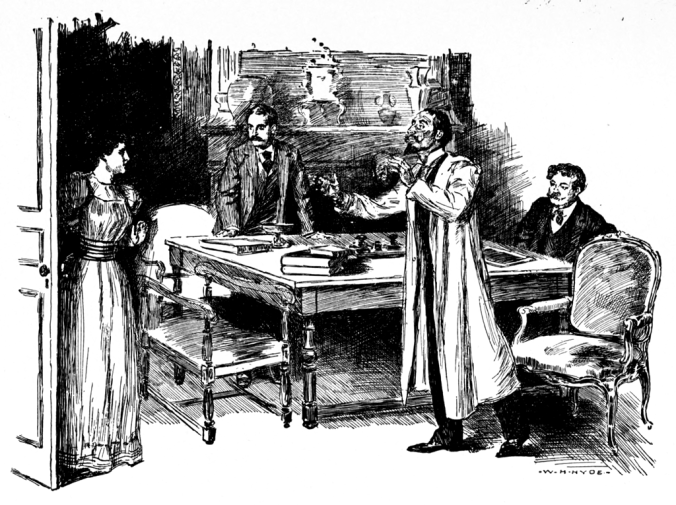

The prince called in the Vienna police; their investigation turned up Johann Peter’s name. When interviewed, Peter claimed the skull had been given to him by the now-dead Dr. Eckhart, who had told him it was Haydn’s but had not told him how he had procured it. Peter apologized, telling police that had he known Eckhart had obtained the skull illegally, he would have turned it over to authorities immediately. Then he handed the officers a skull. When Rosenbaum was questioned, he gave police the exact same story, and for a time, the police were satisfied.

Haydn Skull Switcheroo

Later examination of the skull that Peter handed over showed that it could not have been Haydn’s, as it was the skull of a young man. Rosenbaum’s house was searched, but police turned up nothing. Prince Nicholas, embarrassed by the bad press the whole affair was causing, offered Rosenbaum a bribe to turn over the real skull. Rosenbaum did hand over another skull, which seemed to be that of a man Haydn’s age, and this skull was shipped to Eisenstadt and interred with the rest of Haydn’s remains.

The Real Skull Makes the Rounds

But the skull buried in Eisenstadt was not the one Haydn had possessed in life. Rosenbaum had in fact stashed the real skull in a mattress when the police came to search, and then had his wife Therese lay on it, knowing the officers would never ask a lady to get out of bed. Rosenbaum kept the skull until his own death was approaching, when he turned it over to Peter with the wish that it eventually be given to the Society for the Friends of Music. When Peter died, his wife tried to give the skull to the Esterhazy family, but ironically the family would not take it, as they thought Haydn’s skull was already in its tomb.

The skull of Joseph Haydn passed to Peter’s physician Karl Haller, who gave it to his mentor, famed pathologist Carl von Rokitansky. In the 1890s, the skull finally made its way to the Society for the Friends of Music. In 1946, another attempt was made to return the skull to Eisenstadt, but it wasn’t until 1954 that Haydn’s wandering skull was finally reunited with the rest of the composer’s mortal remains.

Source:

Dickey, Colin (2009). Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius. Unbridled Books. ISBN: 9781932961867.