Awesome site Ginger Nuts of Horror have posted a short interview with me! Please have a read here, won’t you?

horror

“Red Menace” Book Trailer

“Red Menace” Cover Art

Release date for “Red Menace”

My new novel Red Menace, a potent brew of old-school witchcraft, Edgar Allan Poe, and serial murder, will be published by Damnation Books on October 1st. Please check it out, won’t you?

News on my upcoming novel, “Red Menace”

Today I received the review copy of my novel Red Menace from the senior editor at Damnation Books. It will be my last chance to make corrections before it goes to press, so I’m going to spend tomorrow going through it with a fine-toothed comb. Haven’t got a definite release date yet, but the editor says it will likely be October or November. Keep watching this space!

Excerpt from “Understanding the Reanimated”

The full short story appears in my 2011 book, The Associated Villainies.

Daisy swayed back and forth in her chair, a thin stream of drool hanging from the corner of her mouth. She appeared not to notice it, and she appeared not to have heard Dr. Jenner’s question, so he gently repeated it.

“Why do you want to eat human flesh, Daisy?”

Her eyes seemed to meet his for a moment, and he drew in his breath, for he swore he’d seen a spark there, though of what he couldn’t be sure. Was it simply hunger? Or the effects of the drug the nurses came to inject every four hours? Or could it have been something else, perhaps nothing as profound as intelligence, no, but maybe a kind of rudimentary understanding at least… He didn’t want to get too excited; it had only been a flash, a second, but he couldn’t help his palms moistening.

“Daisy? Can you hear me? Do you understand?” He was leaning toward her now, closer than he should have really—the reanimated were still dangerous, despite the medication, and it never paid to be careless around them. But Daisy seemed far more responsive than any of the other patients he’d interviewed in the clinic. He realized that wasn’t saying much, but in this case he’d take what he could get.

She was swaying endlessly, like a snake looking for a place to strike. All of them did that, and he assumed it was simply a manifestation of their condition, filtered through the pharmaceuticals they were forced to take by law. She still didn’t speak—none of them did, or at least they never had when live humans were around—but her strange eyes were fixed on his again, and this time they didn’t simply drift away but held there, seeming to focus sharply behind their milky lenses. Dr. Jenner felt his pulse beginning to race.

“You do understand me, don’t you,” he said, whispering as if the two of them were sharing some delicious secret. “This could change everything.”

He sat there for another hour, firing questions at her and still getting no answers, but becoming more and more certain that he was getting through to her on some level, which was far more than he could say about any of the others. When he finally left the clinic, he called out a musical goodbye to Vera at the nurse’s station. “Any luck today, Doc?” she asked him.

“Yes, Vera, I think my luck is improving. You will call me immediately if any of them say a single word, won’t you?”

“You know I will. Have a good one.”

“Indeed. Good day, Vera.” Dr. Jenner left the clinic, not noticing the way Vera smiled indulgently and shook her head at his receding back.

Germany’s Waiting Mortuaries

Fears of premature burial prompted the construction of these strange institutions in the 19th Century. The original article I wrote can be found here.

The idea of being interred alive is one of humans’ most primal and unspeakable fears, though its common recurrence in legend and literature betrays a helpless fascination as well. There is probably no way to ever discern how many unfortunate people throughout history have fallen victim to this gruesome fate; it’s likely that the numbers swelled during plagues and other epidemics of disease, as bodies were hurriedly placed into mass graves to forestall contagion. Whatever the actual numbers, it is certain that the problem was clearly widespread enough to cause some societies to take unusual precautions.

Bruhier and the Uncertainty of Death

Debates about the exact moment when a person made the transition between life and death had been raging at least since the days of Pliny, with many criteria being used to determine the difference between a dead body and a living one. But the possibility that fallible medical professionals or family members might mistakenly bury someone who was still alive didn’t fully capture the public’s imagination until the 1745 publication of a book called Dissertation sur l’incertitude des signes de la mort by Jean-Jacques Bruhier.

The book was a translation and expansion upon the work of a Dutch anatomist named Jacob Winsløw, who recommended a series of tests on supposed corpses — blowing pepper into the nostrils, shoving red-hot pokers up the anus, slicing the soles of the feet with a razor — to ensure death before burial. Bruhier’s book repeated these ideas, but also added scores of grim, sordid accounts of premature burials — some well-documented, some repetitions of long-lived folk tales. Additionally, Bruhier took Winsløw’s calls for burial reform even further, arguing that putrefaction was the only sure sign of death, and advocating for a system of “waiting morgues” where bodies could be kept above ground until they began to rot.

The Germans Build the Morgues

Though Bruhier’s ideas were never implemented in France for one reason or another, the massive success of the book ensured a series of translations, including a German one in 1754. This book, along with a similarly themed tome by another Frenchman, François Thiérry, was taken very seriously, discussed at length among German doctors and intellectuals. Beginning in the early 1790s in Weimar, at the behest of influential physician Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, plans began to percolate to construct a Totenhaus, or house for the dead, in every German town.

These first waiting mortuaries were large, stately affairs. Corpses (or supposed corpses) were laid out in their shrouds, watched over by attendants who stared through windows, waiting for any signs of life. The attendants often worked 12-hour shifts amid the pungent stench of rotting flesh, and were not allowed to move from their posts. In addition, each corpse was fitted with a series of strings attached to fingers and toes; the strings all led to a central alarm bell which would ring at the slightest movement. Unfortunately the gases from the putrefying bodies were often sufficient to set off the bell, and there were countless false alarms.

Waiting Morgues Spread Throughout Germany

Throughout the following decades, interest in premature burial was high, and more of these waiting mortuaries were built around the country — Ansbach, Munich, Frankfurt, Berlin. Their architecture became ever more elaborate, with classical columns and marble façades that would rival any church or mausoleum. Many of the mortuaries had separate, fancier chambers for the wealthier corpses, and later morgues upgraded their alarms with ingenious clockwork mechanisms and electric buzzers. The morgues also became something of an odd tourist attraction, even visited by literary luminaries like Wilkie Collins and Mark Twain.

The Heyday for Waiting Morgues Passes

Though similar institutions were established in Copenhagen, Prague, Lisbon, and New York, and though a few of the morgues were still operating in Brussels and Amsterdam as late as the 1870s, Germany remained the center of the waiting mortuary phenomenon. But even there the enthusiasm soon began to wane. For one thing, though the morgues were applauded for their philanthropic aspects, the fact was that few citizens actually wanted to install their loved ones in such places, and some morgues had to close for lack of “customers.” In addition, there was never any solid evidence that any corpse had ever revived after a stint in the mortuary; critics questioned the tremendous expense on something which seemed so unnecessary.

Finally, by the mid-nineteenth century, better medical instruments like the stethoscope were coming into common use, making determination of death easier. Besides that, there was also a slowly evolving movement away from unsanitary “communal” death houses and toward more individualistic inventions like “security coffins” outfitted with air tubes, lock-and-key mechanisms, firecrackers, bells, flags, and sirens.

Source:

Bondeson, Jan (2001). Buried Alive: The Terrifying History of Our Most Primal Fear. W.W. Norton & Co., Inc. ISBN: 039332222X.

A Brief History of the Giallo Film

Born of the pulp crime novels of the 1930s, the giallo came into its own on screen, culminating in classic films from legendary Italian directors. The original article I wrote can be found here.

An American writer is walking the streets of Rome one night when he passes an art gallery with enormous glass doors. Peering inside, he is shocked to see a woman struggling with a black-clad figure holding a knife. The writer rushes to help, but when he passes through the first door of the gallery, it closes and locks behind him, while the second glass door before him will not open at all. Trapped in the space between the glass panels, he can only watch in helpless horror as the black-gloved killer plunges the knife into the woman’s body.

This opening scene is taken from an early example of the giallo film genre, Dario Argento’s The Bird With the Crystal Plumage (1970), which was loosely based on Frederic Brown’s 1950 pulp novel The Screaming Mimi. Giallo as a film style began roughly around 1963; though aspects of the stories and themes emerged from pulp novels, filmmakers were quick to add their own ingredients to the mix.

The Origins of the Giallo

Giallo is the Italian word for yellow, which was the predominant color on the covers of the pulp crime novels published by Mondadori, starting in 1929. Following their success, other publishing houses began getting into the act, starting their own lines of cheap mystery novels with yellow covers. These were so popular during the 1930s that the word ‘giallo’ became synonymous with crime and mystery fiction.

The First Giallo Films

It soon became apparent that the medium of film could be used to add interesting elements to the straightforward crime stories from the novels. Taking several pages from Alfred Hitchcock’s playbook and spicing things up with elements of eroticism, horror, and madness, legendary director Mario Bava made what is generally considered the first giallo film, 1963’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much. The plot revolves around a murder witness who is tormented by an important detail that she can’t quite remember. The following year, Bava followed with the now-classic giallo, Blood and Black Lace (known in Italy as Sei Donne Per L’Assassino, or Six Women for an Assassin), which featured a masked and gloved killer stalking the catty and underdressed models at an upscale fashion house. By this point, the particular tropes of the giallo were becoming de rigueur, and the early 1970s saw a flood of films that displayed variations on the theme.

Conventions of the Giallo Film

Films designated as giallo are usually murder mysteries, but they have many features that distinguish them from straightforward crime stories or police procedurals (which are known in Italy by a different name, Poliziotteschi). First of all, the murders that occur in gialli are often grotesque and horrific, and are filmed in artful, operatic, or even disturbingly erotic ways, with much spilling of blood. The killer in the 1972 film What Have You Done to Solange?, for example, dispatches his usually nude victims by plunging knives into their vaginas.

In addition, the structure of the films is often baroque, and sometimes contains dreamlike imagery. The killer almost always wears black leather gloves and usually a black trenchcoat or raincoat. The weapon of choice is nearly always a shiny and suitably phallic knife. A giallo’s plot often deals with an unlucky person who witnesses a crime and then spends the remainder of the film struggling to remember some aspect of the scene that they have forgotten or cannot make sense of. The psychological motivations of the killer nearly always have to do with madness or revenge triggered by childhood traumas, lending gialli a hint of gothic horror in juxtaposition to the more modern slasher-type violence that is usually featured. Finally, the films generally have a Grand Guignol feel, and tend to have bombastic or unusual film scores containing free jazz or prog-rock, for example.

Examples of the Giallo Genre

Genre pioneer Mario Bava, in addition to his first two gialli, made two other films in this line, 1970’s Five Dolls for an August Moon and the 1971 classic Twitch of the Death Nerve. Dario Argento has returned to giallo perhaps more than any other director, turning out films like The Cat O’Nine Tails (1971), Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), Deep Red (aka Profondo Rosso, 1975), Tenebrae (1982), and Giallo (2010).

Lucio Fulci, a cult figure in America for his grisly zombie films, made movies in nearly every imaginable genre, and giallo was no exception; his psychedelic Lizard in a Woman’s Skin was released in 1971, and was followed by 1972’s Don’t Torture a Duckling, the understated mystery The Psychic (aka Murder to the Tune of Seven Black Notes, 1977), and 1982’s New York Ripper. Other directors who tried their hand include Umberto Lenzi (Knife of Ice, 1972; Eyeball, 1974), Michele Soavi (Deliria, 1987), and Pupi Avati (The House With Laughing Windows, 1976).

Sources:

Palmerini, Luca M. & Gaetano Mistretta (1996). Spaghetti Nightmares: Italian Fantasy-Horrors As Seen Through the Eyes of Their Protagonists. Fantasma Books. ISBN: 0963498274.

McDonagh, Maitland (1991). Broken Mirrors Broken Minds: The Dark Dreams of Dario Argento. Sun Tavern Fields. ISBN: 095170124x

Victorian Spirit Photography

To a public entranced by the seeming magic of photography, capturing ghosts on film was par for the course. The original article I wrote is here.

It seems hard to imagine in this modern era of ubiquitous digital photography and cheap photo manipulation software, when creating a picture of a ghost (or anything else) is as simple as clicking a mouse; but to the Victorians, the realism of the photographic image seemed incredible and, somewhat ironically, rather mystical. The art of photography was to them a way to miraculously stop time, to forever embed memory in concrete form. Given this perception, it was probably inevitable that people of the era would initiate not only a demand for photographs of corpses, but also a brisk trade in supposed pictures of the spirits of the dead.

Louis Daguerre and Early Photography

Photography as a medium grew out of scientific experimentation in optics and chemistry. The earliest photographic images were made by placing objects (such as plants or fossils) onto light sensitive paper and then exposing the paper to the sun. William Henry Fox Talbot produced the first examples of these, and later Louis J.M. Daguerre experimented with similar images before going on to develop the “daguerreotype,” the forerunner of the modern photograph.

Because of the nature of early photography — passive camera operators, long exposure times — it was widely felt that a photographic image was a completely objective record, untainted by human bias. Additionally, Eadweard Muybridge’s famous photographic series of a galloping horse demonstrated that the flat, uninvolved gaze of the camera could capture things the human eye could not see; in the case of the horse, this proved to be the fact that all four of the horse’s hooves were off the ground simultaneously at some point during the gallop. These two aspects of the new technology — both its supposed scientific inviolability and its ability to freeze images invisible to the human eye — contributed to its use in the sciences as well as among adherents of the new religion of Spiritualism.

Spiritualism, Seances, and Photographing Ghosts

The rise of Spiritualism in the 19th century coincided with the waning of traditional religious belief and the flowering of the Enlightenment, when people began to realize that science could be used as a tool to solve problems that had vexed humanity for millennia. Spiritualists, even while they attempted to speak to the dead at seances and shrouded themselves in paranormal trappings, saw themselves in a decidedly scientific light. They reasoned that since science had uncovered and explained invisible “forces” animating the universe — electricity, magnetism — science would also soon explain “life forces” that survived the body after death. Photography played a large part in their supposed “experiments” aiming to prove the existence of ghosts.

Early photographers were of course aware of the faint ghostly images produced when the subject of the photograph moved while the plate was being exposed. It isn’t clear who was the first photographer to use this quirk as a means to make spirit photographs, but one of the most famous was William Mumler, who in 1861 began producing spirit photographs in his Boston studio. Likely using double exposures and various other tricks, Mumler made quite a comfortable living taking pictures of grieving sitters with ethereal friends and relatives hovering nearby. He even took the infamous photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln in which the supposed spirit of her assassinated husband stands behind her with his hands resting on her shoulders.

Mumler’s fame was so widespread that he soon came under scrutiny from authorities, who eventually charged him with fraud — not because his pictures were not really of ghosts, which of course they weren’t, but because the blurred images of the “spirits” in the photographs were not usually recognizable as the friend or relative of the living sitter.

Photographic Fakes and the Culture of Mourning

While the Victorians were quick to accept the reality of the spirits in the photographs, believing as they did that photography was resistant to human manipulation, the truth is that the pictures were fakes, in most cases rather clumsy fakes. Like that other Spiritualist trope, the seance, which was performed through cunning trickery and hidden accomplices, spirit photography stood as a testament to creative fraud, an attempt to bolster people’s deeply held beliefs through managing their perceptions of reality. The culture of death and mourning prevalent in the Victorian era combined with a new attachment to the objectivity of the scientific method produced a strange hybrid of materialism and metaphysics whose reverberations can still be felt to the present day.

Source:

Firenze, Paul. “Spirit Photography: How Early Spiritualists Tried to Save Religion by Using Science.” Skeptic. Vol 11 No 2. 2004: 70-78.

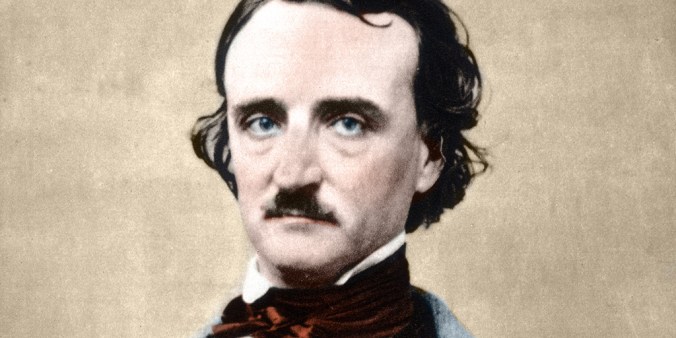

Edgar Allan Poe and the Murder of Mary Rogers

This is an article I wrote a while back about the real case that Poe used as an inspiration for his story, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt.” The original article appeared here.

Tragic American scribe Edgar Allan Poe, while most popular today for his gruesome horror stories, in fact wrote successfully in many genres and is generally credited with pioneering the modern detective story through the invention of his fictional sleuth, C. Auguste Dupin.

Several of Poe’s stories were partly based on true events, but one of the most intriguing examples was the detective story “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” inspired by the brutal 1841 rape and murder of a pretty twenty-year-old woman in New York City. There has been rampant speculation as to what happened to Mary Cecilia Rogers, the “real” Marie Rogêt, but even now, almost 170 years after her death, her killer remains unidentified.

The Disappearance of Mary Rogers

It was on the morning of Sunday, July 25, 1841 that twenty-year-old Mary Cecilia Rogers told her fiancé Daniel Payne that she was going uptown to visit her aunt. Mary, by all accounts a stunningly beautiful young woman, was clad in a white dress with a black shawl and a blue silk scarf, her black hair tucked under a flowered hat. Daniel Payne agreed to meet Mary at the omnibus station when she returned from her aunt’s house later that evening. But Mary Rogers would never be coming back.

Payne, alarmed when Mary had not returned by Monday, placed a missing persons ad that ran in Tuesday’s New York Sun. Upon hearing of Mary’s disappearance, a former sweetheart named Alfred Crommelin also joined the search. It was Crommelin who, on Wednesday the 28th, saw the commotion around the Hudson river, where a woman’s body had been pulled from the water. Crommelin initially identified Mary by the presence of a birthmark on her arm — the face was too battered for easy recognition — and Mary’s mother later identified the clothing the girl had been wearing when she’d last been seen alive.

An Unlikely Drowning and a Range of Suspects

In the early stages of the investigation, it was thought that Mary Rogers had simply drowned, but even a peremptory examination of the body demonstrated that Mary had obviously been dead before going into the water, which of course pointed to murder. Payne and Crommelin were naturally questioned, though both had unimpeachable alibis, as did Mary’s former employer, tobacconist John Anderson, and all of her other friends and fellow residents at the boarding house where she lived. In the absence of a clear suspect, rumors began to circulate almost immediately.

A Clandestine Abortion

One of the most insidious of these was that Mary had died either during or shortly after a botched abortion, and had been disposed of to cover it up. This tenacious rumor was based on the alleged confession of a tavern keeper who had supposedly seen Mary in the presence of a physician and knew that the abortion had been performed in his tavern. The “confession” turned out to be completely fabricated, but the abortion story not only turned up in a later revision of Poe’s fictional account of the crime, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” but continued to be repeated as truth in several books about the murder, right up into the modern day. It was also apparently a factor in abortion becoming criminalized in New York State in 1845.

The Suicide of Daniel Payne

Though Payne was quickly dismissed as a suspect, new stories began swirling about his involvement after he took his own life in October of 1841, by taking an overdose of laudanum. A cryptic suicide note was found in his pocket that some interpreted as a confession, but the note could also be read as simply a statement of grief, an unwillingness to go on living after Mary’s death. Indeed, Payne’s friends claimed he had been inconsolable after the murder, and were not terribly surprised that he would take such drastic action.

Who Really Killed Mary Rogers?

It was clear that someone had murdered the girl, but the mystery of who had done it was becoming murkier. In Poe’s story, the killer is thought to be a naval officer, perhaps the fictional counterpart to Mary’s real-life fellow boarder, sailor William Kiekuck, who was questioned about the crime but had a solid alibi. There was also speculation that Mary had been set upon by a gang; initial autopsy reports stated that Mary had been “violated by more than two or three persons,” though later investigation suggested otherwise.

In a recent article in Skeptical Inquirer, Joe Nickell analyzed the many books and articles written about the unsolved murder, and also went back to revisit contemporary news stories and police reports. His conclusion, also reached by other scholars, was that Mary was likely raped and killed by a single assailant, an unidentified “swarthy” man who a few witnesses saw walking with her shortly before her disappearance.

She was raped and then strangled with a piece of lace trim; her unknown murderer then tore a strip from her petticoat and used it to fashion a sort of sling which he used to drag the body to the river (this fact alone casts doubt on the gang-rape theory, as a group of men could have easily carried the body). Whoever he was, the man who killed Mary Rogers evidently got away with his crime. Mary herself lives on in the pages of Poe’s masterful fiction.

Source:

Nickell, Joe. “Historical Whodunit: Spiritualists, Poe, and the Real ‘Marie Rogêt'”. Skeptical Inquirer July/August 2010: 45-49.